What We Learn in the Kitchen: An Introspection on the Black Queer Daughter

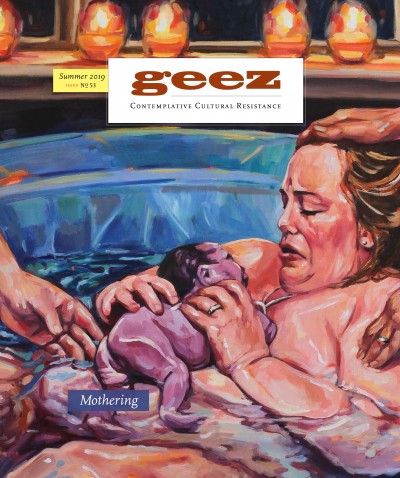

With Woman Credit: Amanda Greavette (link below)

“My mother connects me to a past I would have no other way of knowing. And in this sea of whiteness, of friends, enemies and strangers, I look at her and know who I am.”

– Michèle Pearson Clarke, Transition

Two minutes into a phone call with my mother and she has launched into a full review of her church’s leadership transition, recounting details of a recent board meeting in which she was obliged to provide her unique clarity.

“Visionaries need me, they can’t explain what they want but I can see it. If you shut up and leave me alone, I can make it happen.”

We go on to chat about a young family friend who just broke up with her first girlfriend.

“It’s a big mess. This is why God never designed women to be romantically involved with other women. Too many emotions.”

“Mother, she’s 18. Of course it’s not going well. She’s a kid.”

“Yes, she’s young, dumb, and immature. And you’re older, dumber, more immature, so what’s your point?”

I wince as her words sting a little more than I would have expected. All of sudden tears spring into my eyes and I take a deep breath. A force of habit, I take a step back and focus.

For better or worse, most of the conversations I have with my mother about faith or my sexuality happen in her kitchen. Today, even though we’re about 600 miles away, I can hear her continuing the tradition in her “office,” as she calls it. Despite the argument we’re having, knowing she is there comforts me. There is something about that special space that seems to bear the brunt of emotionally fraught conflicts with the strength of decades.

Historically, the kitchen has been a place of connection for mothers and daughters representing the bonding ritual of food provision and the passage of cultural legacy and family tradition. Maybe it’s all part of patriarchal construct, or maybe it is the deeply bonding ritual of rite of passage and magic weaving.

In Zami: A New Spelling Of My Name, Audre Lorde explores memories of her mother’s kitchen through recounting the feel and rhythm of a West Indian mortar and pestle and the sharp smell of garlic and celery leaves.

In describing her mother’s larger-than-life presence in her kitchen, she identifies it as a conduit through which to receive that warmth of attachment that can sometimes evade powerful matriarchs.

“Sometimes my mother would look over at me with that amused annoyance which passed

for tenderness.

What you think you making there, garlic soup?

Enough, go get the meat now.” (Lorde, 1982)

The sardonic yet tender correction seems to faintly mask a more potent instruction: learn our way accurately, preserve our legacy.

I think of my own memories of my mother’s kitchen and her admiral-like presence in it – noting the same subconscious messaging on how to keep our legacy alive. She raised us on red beans and rice, chili, Jambalaya, Gumbo; dishes reminiscent of her mother’s Southern/Creole heritage. When I ask during our conversation if this was a conscious effort, she at first says no: “I cooked the food that my mother endeared to me because I liked it and it was good for you!”

Later in the conversation however she reveals that she had an early desire to equip her children with the skills to prepare and provide food for their own families. As a result, the emotional connection she had with the kitchen, due mostly to her grandmother, was transferred to my brothers and sisters and I, tying us inextricably to her past. We came to know her kitchen as a proverbial resting place just as much as a physical one. I didn’t realise it for a long time, but this was what I feared losing most by coming out.

As queer women of colour, this is the question that consumes us, whether consciously or not. Have we disqualified ourselves from that archetypal birthright of transference and affection? Have we lost our right to this essential attachment and our legacy?

Conversations with other queer women of colour have given texture to these questions of loss. I spoke with Ashley Brown, a proud, biracial queer woman. Brown recalled how her sexuality, though a beautiful revelation to herself, initially drove a wedge between her and her mother.

“At first I tried to will myself into submission, not wanting to lose something so important.”

But when the moment eventually came to confront that possibility of loss, it didn’t go well.

“I came out to my mother at 19 while we were baking cookies together for a church drive – a tradition of ours. I told her I had met someone, and that her name was Kayla.”

The ensuing silence was deafening.

“She didn’t say anything or look at me. She simply put her cookie cutter down, went upstairs to her room, and closed the door.”

The silence continued for over a year. When dialogue did revive there was no apology, but there was a desire to make amends.

Brown and I both found that, in situations like these, our mothers did not seem to know how to apologize – or even what to apologize for. In the case of Brown’s mother, apologizing would mean admitting fault to her daughter – something she didn’t know how to do.

When I spoke to my mother about what she experienced when I came out, she described her own sense of loss. For her it was a loss of spiritual partnership, and a loss of trust.

“Most of the time kids don’t know when they’re wounding their parents. You have to give room for failure and know it will be painful.”

After the emotional rollercoaster of telling my parents I was dating a woman, it wasn’t until the next time my mother cooked for me that I could feel she still loved me. Our competing beliefs about scripture and the nature of God did not disappear, but there was an element of spiritual and emotional healing.

Trayce Bell Brooks, a close friend of my mother’s, learned her way around the kitchen from her father. When he passed she used cooking as a way to feel closer to him, a way to preserve their relationship. Years later, Brooks is learning how to preserve her relationship with her own daughter who recently came out to her as queer.

“The most important thing to me right now,” she tells me over the phone, “is to listen.”

“Put everything on pause, open my heart and really listen. I feel like I didn’t understand her in the way that I needed to and that she needed me to. It has motivated me to go deeper with her.”

This isn’t easy, as Brooks holds a similar viewpoint to my mother as to the peccancy of same-sex relationships.

“[She] is my first daughter, so of course I think about grandchildren and what will happen with that.”

This, however, doesn’t stop Brooks from driving up to her daughter’s university and taking her out to dinner to talk, listen, and walk the “tightrope” that she calls this new learning period. The element of food and shared palettes brings a sense of comfort to the conversation. Her worries about this new world of queerdom are not gone, but neither is her daughter. It is simply now her turn to learn.

Kendall M. Waterman is a freelance writer/film editor originally from Detroit, Michigan, currently living in New York City. She is the creator and co-host of the podcast TalkTime, wherein she and her mother (heavily) debate questions on religion and sexuality. Also, she’s queer as hell.

Image credit: Amanda Greavette, “With Woman,” 2017, oil on canvas, 42 × 34, The Birth Project.

Dear reader, we welcome your response to this article or anything else you read in Geez magazine. Write to the Editor, Geez Magazine, 1950 Trumbull Ave Detroit, MI 48216. Alternately, you can connect with us via social media through Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram.

Start the Discussion