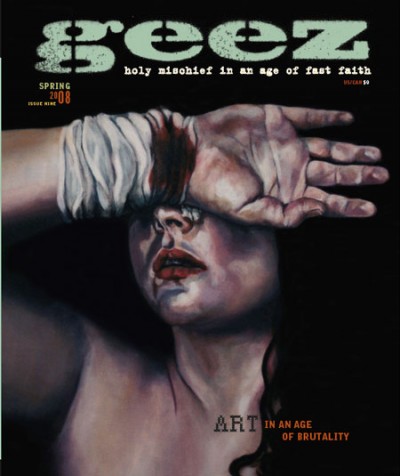

Maybe art

See Plants on cars and more in the Art Digest

Can art save the world? Well, I suppose it can. But, then again … no, it probably can’t.

Confused?

Okay, sorry for the mixed message, but this ambivalence comes from my sense that art is fundamentally neutral. That is, art is just a commodity, one with enormous cultural value, for sure, but a commodity all the same. There’s nothing inherently subversive about it.

Now, I’m perfectly aware of – and tip my hat to – the legions of artists using their art as a tool for positive social change. But given how much vapid art is out there perpetuating the dominant materialistic status quo, what’s the sum total of art’s impact on the world? And moreover, what do we mean by art? Is it just the masterpieces that hang in our eminent galleries and museums? Or does it include so-called “low art”: paint-by-number kits, China plates emblazoned with Princess Di’s beaming face, mini-busts of angels, Precious Moments and Hummell figurines?

I make the point because even though you’ve likely never heard of Sam Butcher – creator of the Precious Moments empire, an unstudied figure in art schools – he is an artist by any measure. And he presides over a multi-million dollar business enterprise that floods the world with cutsie crap that is so perfectly emblematic of the vacuous consumerist binge that’s driving the Earth to the brink. Well, that’s what I think, anyway.

But even if we separate so-called low art from the equation, there are still plenty of artists who are simply shilling a profitable commodity without any genuine interest in bettering society.

Hirst

We have the likes of Damien Hirst, a “Young British Artist” worth nearly $250 million. For those keeping track, he was paid $100 million for a diamond-covered cast of a human skull and Levi’s brought him on board to produce a line of designer jeans.

Another example might be photographer Cindy Sherman, who created a series of ads for Marc Jacobs and is on board with Nike’s iD studio. My favourite, though, is Takashi Murakami. He reads Bill Gates for management tips and sells anything and everything: paintings, sculptures, videos, T-shirts, key chains, mousepads, plush dolls, cell phone caddies, and – wait for it – $5,000 limited-edition Louis Vuitton handbags. He told the New York Times, “Just like with Warhol soup cans or Marilyns, if there is a need in the market, I can put them out. The gallerists worry that if there are too many, the value will go down and their auction prices will be low. But I don’t think so. If there is a demand, I will keep making them.’‘

Don’t get me wrong. Obviously I don’t think artists have to starve to be legit. My point is simply that never mind the moneyed elite who snatch up high art, there is an abundance of artists themselves who embrace excess and the hyper-materialistic ethos that seems to rule the day. So we may be disappointed if we’re expecting the art world to save the world.

See The Encampment and more in the Art Digest

Bound

Ultimately, even those artists who do use their craft as an agent of social and political change are bound by the same limitations that bedevil the rest of us. Picasso’s Guernica is a stunning and powerful reminder of the devastating effects of war, but seven decades later, innocent civilians are still being cut down by bomb-laden killing machines. Perhaps a more telling example is the contemporary genre of Chinese Gaudy Art. What appears at face value to me as a clever critique of China’s get-rich-quick orgy of consumption is in fact, according to art critic Li Xianting, demonstrative of “the powerlessness of art to impact on the pervasiveness of consumerism in today’s reality.”

I’m even resigned to the fact that my absolute favourite artist, British provocateur Banksy, is extremely limited in what he can achieve with his politically charged graffiti. Banksy’s satirical stenciling is a brilliant and cheeky take on war, capitalism, public surveillance, and general establishmentarianism. One of his more famous acts of civil disobedience consisted of a trip to the West Bank to deface the Israeli separation wall with images of escape and tantalizing views of what must lay on the other side.

It’s inspiring stuff – and pretty damn funny too – but the steamroller that is the Israeli military likely didn’t give the paintings a second glance. I’m convinced Banksy’s actions provide some intangible value, but in concrete terms, it’s hard to argue that Palestinians are any better off. Not that Banksy claimed they would be.

None of which is to say that Banksy et al. should call it a day because they’re not having an impact. They are. It’s just that art, like anything else that inspires us, can’t be subjected to a cost-benefit analysis. We can’t know its ultimate impact.

Essentially, my simple proposal is that when it comes to saving the world, broad-based, grassroots political mobilization is probably our best bet. Artists, just like everybody else, should be encouraged to plug in wherever they can. But so should dentists, gardeners, accountants, teachers, bus drivers, morticians, and, hell, maybe even the odd writer or two.

Nicholas Klassen is a former senior editor at Adbusters magazine and a principal at Biro Creative in Vancouver, British Columbia

Sorry, comments are closed.