Daniel Berrigan, Poetry Incarnate

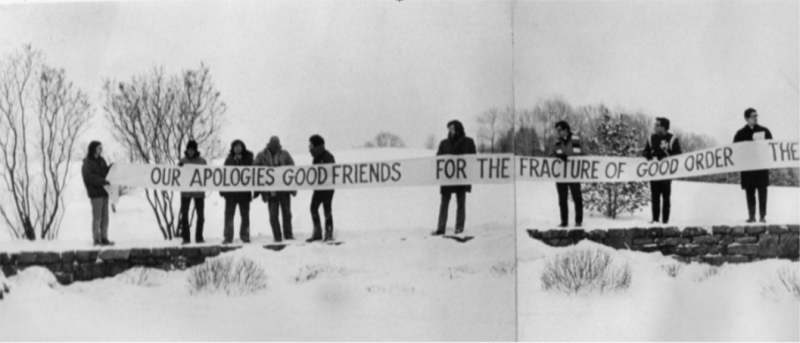

Daniel Berrigan's release from the prison in Danbury, Connecticut, February 24, 1972 Credit: Jim Forest CC (link below)

Kurt Vonnegut once quipped, “For me, Daniel Berrigan is Jesus as poet.” For Berrigan, poetry was mode and method of survival.

You are jail-yard blooms,

You wear bravery with a difference.

You are born here will die here;

Making you, by excess of suffering

And transfiguration of suffering, ours.

Between life as fools pace

and life as celebrant’s flame – aeons.

Yet, thank you. Against the whips

Of ignorant furies, the slavish pieties of judas priests

You stand, a first flicker in the brain’s soil, the precursor

Of judgement.

Dawn might be, we might be

Or

Spelling it out in the hand’s palm

Of a blind mute

God is fire, is love

With permanent marker, in his distinctive hand, Daniel Berrigan, poet and priest, covered the dining room wall of our little hospitality and resistance house in Battle Creek with this portion of “Tulips in the prison yard.” It was a blessing and virtually a call to discipleship. The house and wall are gone altogether, but still I know it by heart.

The poem stems from his own imprisonment for burning draft files in Catonsville, MD as a protest in 1968 against the war in Vietnam. The non-violent direct action by nine Catholics was distinctive for implicating the church in the anti-war movement (Dan and his brother Phil appeared in collars on the cover of Time) but even more so for casting the action in the poetics of liturgy. Dorothy Day termed it an “act of prayer.” William Stringfellow was even more specific: “a politically informed exorcism.” It took direct action to another discipline and dimension – of word and spirit.

Dan drafted, what to even call it, a press release? action statement? movement missive? in language to become a masterpiece of spiritual/political/poetic writing. A portion here:

There we shall of purpose and forethought

remove the 1-A files sprinkle them in the public street

with home-made napalm and set them afire

For which act we shall beyond doubt

be placed behind bars for some portion of our natural lives

in consequence of our inability

to live and die content in the plagued city

to say “peace peace” when there is no peace

to keep the poor poor

the thirsty and hungry thirsty and hungry.

Our apologies, good friends,

for the fracture of good order, the burning of paper

instead of children, the angering of the orderlies

in the front parlor of the charnel house

We could not so help us God do otherwise

For we are sick at heart. Our hearts

give us no rest for thinking of the Land of Burning Children.

Dan’s testimony at the Federal trial reiterated the statement, but more to the point, the trial was altogether one with the moral and poetic trajectory of the action. The jury may have convicted the Nine, but Daniel published the court transcript of their testimonies, with pertinent prose quotations inserted (Camus, Brecht, Neruda, Fidel, Ho Chi Minh), as a play in free verse which has been produced internationally and filmed, and which is currently in revival on a New York stage. It is set before another jury of conscience: ourselves.

Berrigan’s testimony in the dock recounted how he came, step by step, in conversion of conscience to Catonsville. Two events were most excruciating and immediate. One was the anti-war self-immolation of a young man in Syracuse, whom he visited in the hospital room before his death (see his discussion on this topic with Thich Nhat Hahn in The Raft Is Not the Shore, Beacon, 1975). The other, in Hanoi to retrieve captured American soldiers, he crouched in a bomb shelter beneath the onslaught of U.S. B-52’s. In fact, the last words of the defense summation to the jury are another poem of Dan’s telling that moment with “children in the shelter.”

I picked up the littlest

a boy, his face

breaded with rice (his sister calmly feeding him

as we climbed down)

In my arms fathered

in a moment’s grace, the messiah

of all my tears. I bore, reborn

a Hiroshima child from hell.

Members of the jury, what say you?

While awaiting an appeal, Daniel Berrigan read and reviewed Eldridge Cleaver’s Soul on Ice. He was struck by the “new language” the Black Panther invented in prison, refusing the method those in power call “civilized discourse” – “adopted almost universally by the little gray men in glasses who make the decisions about the many who shall die and the few who shall live, from Harlem to Hanoi.” Resistance required a new idiom, a shift in the very elementals of thought and speech. Cleaver’s new method:

…has something has to do with the soil in which the mind of man grows. The soil today is stony indeed, a combination of prison rock, macadam, ennui, unreason, enclosure, the stifling threat of violence, mindlessness. No matter. What we are talking about is prophetic discourse, fury in the face of repression… (National Catholic Reporter, March 19, 1969)

Was it a self-conscious preparation for his own pending prison discourse? Perhaps. But first a poet’s interlude. Berrigan declined to submit himself for prison, slipping away in front of U.S. Marshalls at a public event, clothed in the giant puppet of a disciple in tableau at the Last Supper. You can’t make this stuff up. For five months he haunted the nation underground – harbored, preaching, interviewed on national television, corresponding publicly and writing poetry from J. Edgar Hoover’s 10 Most Wanted list.

For the “Feast of Bonhoeffer,” on Eberhardt Bethge’s then new biography, six pages of verse in The Saturday Review:

I begin these notes on 9 April 1970. Two hours ago, at 8:30 A.M.,

I became a fugitive from injustice, having disobeyed

a federal court order to begin

a three-year sentence for destruction of draft files two years ago.

It is the twenty-fifth anniversary of the death of Dietrich Bonhoeffer

in Flossenburg prison, for resistance to Hitler.

The temperature outside is 64. It is a foggy, wind-driven day

well tempered to my mood

But let me begin at the beginning.

My theme, as Bonhoeffer would put it, is faith and obedience.

He said: Invisibility breaks us to pieces. Again:

Simply suffering; that is what will be needed—not parries or blows

or thrusts. The real struggle which perhaps lies ahead

must consist only in suffering belief.

And again: The task is not only to bind up the victims beneath

the wheel, but also to put a spoke in that wheel.

By August, exhausted and hoping for some quiet days to sit still, to talk and write, he was arrested by the FBI, posing infamously as birdwatchers, at the Block Island home of William Stringfellow and Anthony Towne. He would recall:

How’s this for a time warp?

Year’s gone, the maladroit

Malodorous bird watchers poked about. I sat in the yard

Storms gathering, slicing country apples.

They pounced, the bird was nabbed!

That scene, domestic, hilarious, once & for all foreclosed.

Bill gathered the remnants, that nothing be lost.

Two years went by; then

Return of the native!

Welcome, spectacular banquet;

Dessert? Resurrected apples,

Deep dish pie!

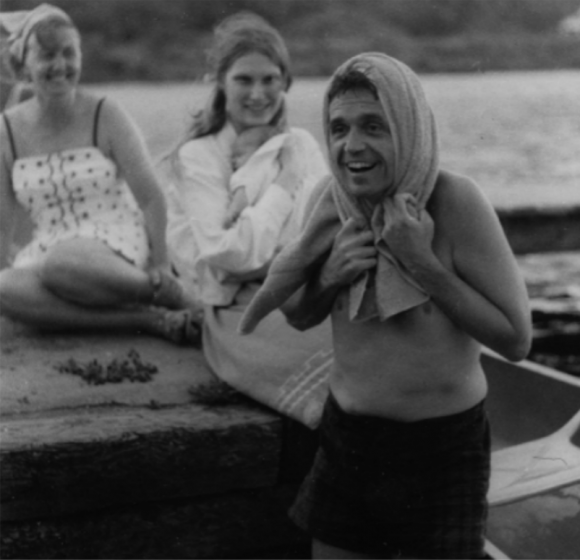

Daniel Berrigan, baptism, 1967 Credit: Jim Forest CC (link below)

Resurrection was an experience of his prison time (Stringfellow remarked on this freedom of Dan and Phil during a visit in 1970). Most explicit in this regard is “The Risen Tin Can.” At the back of Danbury Federal Correctional Institution Berrigan observed and heard a machine for crushing flat the metal refuse of the kitchen. It struck as a stand in for the very function of the place upon its inhabitants. Here but a glimpse:

We prisoners are, so to speak, tin cans

emptied of surprise, color, seed, heartbeat, pity, pitch, frenzy

molasses, nails, ecstasy, etc., etc.

destined to be whiffed and tumbled into elements of flatland

recycled, dead men’s bones, dead souls –

Now the opposite of all this is the shudder and drumming feet

of the risen tin can

over the hill, into the sunrise

The tin can contains, grows wings, he writes poetry!_

This is the year of the RISEN TIN CAN, in the Vietnamese sense.

REVOLUTION REFUSAL REBUTTAL POETRY.

When I was a tin can I thought like a tin can I looked like a tin can

I spoke like a tin can

now that I am a man I have put away the things of a tin can

NEMPE [namely]

tin armaments tin hearts tin bells rin-tin-tin gross national tin

American tin. . .

The unforgiveable sin against the unholy spirit

is the metamorphosis of tin into manhood.

Of which one instance: the writing of a poem.

As Dan told Jim Forest, his friend and now biographer, “I should have gone to prison sooner. It’s a pressure cooker of poetry.”

Dan won poetry awards for his early work, but truly some of his best originated in trial, on the run, and in the lockup. Kurt Vonnegut once quipped, “For me, Daniel Berrigan is Jesus as poet.”

For Berrigan, poetry was mode and method of survival. He once recounted that the homilies of the Danbury prison chaplains were so deadly and mind-numbing that he took up the discipline of memorizing T.S. Elliot’s Four Quartets during sermon time at mass. Focusing and clarifying the mind. Upon release he came to NYC to teach a course in the Revelation of John. As students, we could hear the echoes of Elliot in his reading of apocalypse…where “in the end is our beginning.”

In my mind, his best poem from prison is long and little known. A Letter to Vietnamese Prisoners was published by the Merton Center in NYC, with art by fellow prisoner, Tom Lewis. I’ve no doubt it was hand delivered to its intended by way of Nhat Hahn, then exiled in Paris. During the Tiger Cage Fast and Vigil in the summer of 1974, taking a page from Dan, I committed the entire poem to memory while sitting inside a mock tiger cage cell, used for political prisoners in Vietnam, on the steps of the U.S. Capitol. With a little refreshment or prompting I can recite the letter still. Here just its beginning and its end.

Dear friends, your faces are a constriction of grief in the throat

your words weigh us like chains, your tears and blood

fall on our faces. Prison; Vietnam, prison; U.S.

prison is our fate, mothers bear us in prison,

our tongues taste its gall, bars spring up

from dragons’ teeth, a paling, impaling us.

A universal malevolent will, crouched like a demon

blows winter upon us, stiffens our limbs in death, the limbs of

women and children…

It is snowing tonight as I vigil.

The first white fall of winter

bitterly cold. I think on

the fevers and horrors of Con Son.

No their No. YES to all else.

Bill Wylie-Kellermann is a nonviolent community activist, retired pastor, and author living in Detroit. His most recent books are Dying Well: The Resurrected Life of Jeanie Wylie-Kellermann (Case Community, 2018), Principalities in Particular: A Practical Theology of the Powers that Be (Fortress, 2017), and Where the Waters Go Around: Beloved Detroit (Cascade, 2017).

Image credit: “Daniel Berrigan’s release from the prison in Danbury, Connecticut, February 24, 1972,” “Daniel Berrigan, baptism, 1967,” Jim Forest CC, flickr.com/jimforest

Dear reader, we welcome your response to this article or anything else you read in Geez magazine. Write to the Editor, Geez Magazine, 1950 Trumbull Ave Detroit, MI 48216. Alternately, you can connect with us via social media through Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram.

Start the Discussion