A Mother’s Prayer Forward

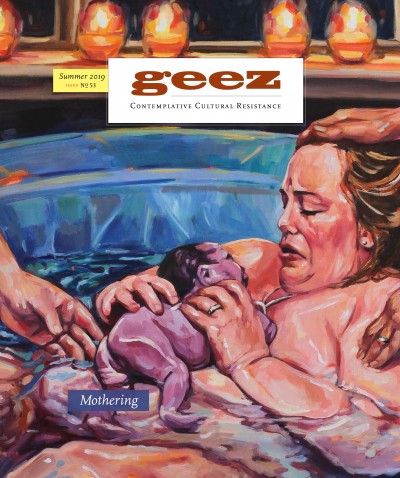

“Nursing at the Tree of Life,” April 2019, Pics/Art graphic collage. Credit: Lucia Wylie-Eggert

It was midnight when I received the call from my sister that my dad, newly home from the hospital after knee surgery, was headed back to emergency with concerns about oxygen intake, infectious swelling, and more. My sister said my dad, with his brand-new, still-raw knee replacement, ran to the car as though the sprint for his life would be worth the pain. Or worse, if he didn’t make it to the hospital, the pain would mean nothing because this was life or death. Death . . . Oh God, I can’t believe how much pain I felt as I took in the news. I let tears fall and they turned to sobs that I choked on as my husband Daniel held me in our bed.

Death was not unfamiliar. My mother fought brain cancer for over seven years and died in 2005. As a family, we were well acquainted with middle-of-the-night trips to the hospital, confusion about warning signs, and the constant pain of preparing for death. But this was the first time I felt that fear with my dad – he was my healthy parent, the rock of our family in his own special way. It was more than I could bear. I wanted to shake off my breakdown as a major overreaction, but I couldn’t quite find the truth in it.

My mind raced and I became haunted by the look of my father from earlier that evening. The family had been overjoyed to bring him home, even though we hadn’t entirely trusted the care and advice he’d received. His discharge felt clumsy and forced – in fact, as my dad’s stay in the hospital took an extra night postop, his surgeon “joked” that my dad was ruining his stats.

I went over to the house to sit with him, make sure his ice pack was fresh, and read to him as he had done for me throughout my childhood. I brought A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle and he listened as the eccentric characters were introduced and the elements of their world took unexpected turns. I noted how my dad was present and sweet but not well. His pain was on his face and in his movements, his breathing was heavy, and worst, his thinking was muddled and his sentences came slowly. I refused to think of my mom in her muddled states. I read on:

A fresh gust of wind took the house and shook it, and suddenly the rain began to lash against the windows. “I don’t think I like this wind,” said Meg nervously.

“We’ll lose some shingles off the roof, that’s certain,” Mrs. Murray said. “But this house has stood for almost two hundred years and I think it will last a little longer, Meg. There’s been many a high wind up on this hill.”

As I read, my dad would slide into ferocious dozes – his head cocked, his mouth open, his tongue loose. The vulnerability of his sleep terrified me. He looked unwell. He looked old.

In the moment, I wasn’t sure if I should look away to spare his naked vulnerability or look on and love him. I decided to take him in and see him honestly. I found unexpected comfort when I realised that I’d seen that profoundly relaxed, loose-lipped face before. My son Ira had worn it as an infant in similar deep dozes – vulnerable, trusting, and tender.

I smiled remembering that when Ira was a smushy, wrinkly little guy I had thought, “Wow, he looks just like a little, old man.” I thought it so often that I had begun to wonder if it wasn’t a coincidence. Perhaps babies look like old folks because, as parents we are unlikely to see our children grow old. We will die. They, we pray, will live on and grow old without us. I thought, maybe my old man baby brings me intimately closer to the end of his life. Maybe it’s a real window into his end even as his life is just beginning.

As I sat in bed processing the hospital news, my thoughts roared like an uncontrollable wind. I became fixated on the image of my father’s limp face and it would flicker and become my son’s and back again, over and over. Two generations of men that I deeply love in their most vulnerable states. I held onto the image and kept it as my focal point to distract me from the moment’s pain and possibility of death.

As the faces flickered, I dug deeper. If babies indeed look like old folks so that their mothers might know them in their old age, then my grandmother had surely seen this face. She’d held her tender baby, heavy with the smush of developing baby body, tightly in her arms and loved his old-man face. With great pain that only a mother can give, she had poured her heart and her dreams into this tiny man whose life was yet to unfold. She’d sing and – with courage – would allow herself to feel his joys and sorrows, highs and lows, lively moments and battles with death. She’d give him to the world to experience them all. She’d take him in honestly and fill him with love. And her love was surely a prayer forward – a prayer that would reach the future.

Suddenly, I felt my grandmother in the room with me. Holding my dad in her arms with his face flickering from old man to smushy baby. Holding me as I pained and prayed, just as she had done for her infant. Rocking her baby in 1949, she may not have seen her son on the way to the hospital, and she certainly hadn’t seen her granddaughter sobbing with the fear of loss, but her prayer encompassed us both, held me tight, and kept me whole in that dark hour. I was not alone.

At the hospital, my dad was evaluated and his safety renewed – he would live on. Thank you, Grandma. Thank you for the united prayers of generations forward and backward for keeping us whole.

Lucia Wylie-Eggert is newly the art director for Geez and lives in Detroit, Michigan. Her Grandma Bea called her “lassy,” left Pooh Bear waiting for her on the steps, and laughed with her eyes closed and all her teeth showing.

Start the Discussion