Reverence for the Sacred Land: A Response to Endemic Violence in Central America

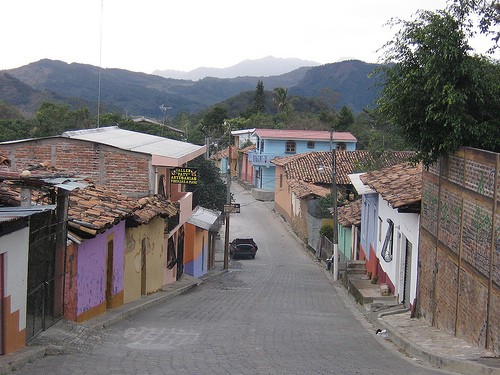

Credit: Shared Interest http://www.flickr.com/photos/sharedinterest/2909885292/sizes/m/in/photostream/

For five years I lived and worked in the outskirts of San Salvador with an organization supporting marginalized families living with HIV/AIDS.

Written by Tobias Roberts

Though the agonizing combination of poverty and HIV formed a part of my daily experience, AIDS was not the main epidemic that surrounded my life. The World Health Organization considers more than 10 homicides per 100,000 residents to be at epidemic levels. From 2004 to 2009, El Salvador ranked first in the world with 62 homicides per 100,000 residents. After five years in San Salvador, having a pistol pointed at your head during an assault on the public buses became a common experience.

Every day after sunset as I returned to the small house I shared with my wife and her family, I went through the same apprehensive routine: Walk quickly through the streets; look constantly over your shoulder to see if you are being followed; sit near the front of a bus next to an elderly lady if possible (they always inspire shelter); don´t look at anyone; don´t talk to anyone; don´t trust anyone.

A year later, I find myself living in a quiet Mayan town in the highlands of western Guatemala. Every day after sunset as I return to the small room that I share with my wife, I go through the same life-enhancing routine: Walk calmly through the streets; stop to chat with the local woman selling tortillas on the corner; pause in dark alley to contemplate the stars and the moonlight silhouetting the surrounding mountains; find a pick up soccer game in the park to join in on; look at everyone; talk to everyone; trust everyone.

The difference between these two daily routines—one marked by fear and violence, the other by trust and tranquility—has made me constantly question how violence evolves, how it becomes entrenched in the daily lives of communities, and most importantly, what is a real, effective response to this violence.

From my experience, there seem to be two main “answers” or “responses” that arise due to the endemic situation of violence: the apathetic response and the de-rooted response.

The apathetic response is a response generated by the genuine fear of impoverished, marginalized communities overwhelmed by the ever-present hostility of their surroundings. This response is characterized by an increased militarization of society, a generalized lack of trust, apathetic resignation to the inevitability of violence, and the loss of capacity to consider life sacred. These characteristics are manifested in the recently and popularly supported political decisions among various governments to send out the military to patrol the streets, the resolve of certain political parties advocating for the death penalty, or by “hard-hand” laws that criminalize youth and “suspect” populations. It is seen when, due to the constant killing of bus drivers for not paying extortion fees to gangs, most bus drivers in San Salvador put a sticker on their windshield reading “Only God knows if I´ll be back”, in essence resigning their fate to the luck of the draw. It is heard in the conversations between people on the streets: “What happened over there?” “Ahh, it´s just another dead person.” Fourteen murders a day in a country the size of Massachusetts numbs the inherent capacity we all have to appreciate life as the most sacred and precious of gifts.

This response is then propagated, expanded and exaggerated by the mass media and manipulated by government and business elites who prefer this simplified and superficial response to violence which is purely reactionary, while turning a blind eye to the underlying, systemic causes of this violence. However, I do believe that though manipulated by mass media and elite sectors of society, and though this response has been shown to be completely ineffective in decreasing violence, it is an understandable reaction by communities affected by this unyielding aggression of violence. Communities faced with daily homicides, rapes and extortions excusably opt for the myopic solution of the apathetic response as a type of survival mechanism.

Then there is the de-rooted response; a response formulated by academic sectors, NGO´s, and people more aligned with the political left. It is a response that seeks to question not just the visible consequences of violence, but uncover the underlying causes of this violence. This response argues that youth delinquents and gang members are victims of an unjust system that denies them educational and work opportunities. It advocates for more policies aimed at re-inserting youth as productive members of society and condemns the militarization and “hard-hand” policies that are implemented by governments and championed by mass media.

Though this response by a sector of society is much more holistic and visionary; though it seeks to correct the causes of violence and not just attack its observable consequences; though it offers a much more realistic attempt to effectively reduce violence, there is one key problem. This response is generally formulated and advocated for by sectors of society that live removed from the daily, callous reality of the violence that affects their country. It is a lot easier to advocate on behalf of youth delinquents as victims of an unjust society when you´re not a victim of extortion, or when you don´t have to fear being assaulted on public transportation, or when you don´t live in a community controlled by local gangs and drug traffickers. Ultimately this response, though well articulated and well intentioned, is divorced from the deep-rooted reality of the majority of the marginalized population.

It is popularly said that, “Where there are only two options, look for a third.” I left San Salvador a year ago without a third option. Intellectually and spiritually I identified with the de-rooted response to violence. But corporally and as a part of community anguished by violence, I admit that the superficial, apathetic response, as a survival mechanism, had its place in my being as well.

Shared Interest http://www.flickr.com/photos/sharedinterest/2909837728/sizes/m/in/photostream/

It was here in the small villages of the Mayan Highlands of Guatemala that the third option began to become clearer. Nebaj, the town I live in, hasn´t always been a peaceful place. In the 1980´s, the Mayan Ixhil people of the region were victims of genocide perpetrated by the army during the internal armed conflict. It is estimated that between 15,000 and 25,000 people were killed during the armed conflict in and around Nebaj. But today, Nebaj is a comparatively peaceful place. What has changed from then until now?

The indigenous mentality of connectedness to their land and their determination to defend that land as a sacred part of their community and collective lifestyle is the single most effective barrier to the propagation of violence in their communities. That which is sacred, cannot co-exist with nor tolerate violence. The most visible example of this mentality I witnessed early last year. After struggling to resist the forced implementation of a mega-hydroelectric project on their ancestral lands by the Italian company ENEL, the indigenous communities of Cotzal (neighboring Nebaj) decided to close access to the construction site of the dam as a way to protest the lack of respect for their rights and lifestyle shown by the Italian company and the Guatemalan government. The response of the government was to send in 700 military and police officials armed with semi-automatic weapons and helicopters to terrorize the local population and force them to open access to the construction site of the dam. Faced with a situation of imminent violence, the community came together, formed a human wall to impede the military and police from further advancing onto their lands, and steadily and decidedly pushed it out of their community.

This mentality of connectedness to a land permeates indigenous culture and mindset. Due to an increasing presence of multinational extractive corporations searching for resources to exploit, this mentality has given rise to a resolute determination to defend their lands and traditional lifestyle. Even the most rural households, though illiterate and with very limited Spanish, can recite the International Labor Convention 169 which states: “The peoples concerned shall have the right to decide their own priorities for the process of development as it affects their lives, beliefs, institutions and spiritual well-being and the lands they occupy or otherwise use, and to exercise control, to the extent possible, over their own economic, social and cultural development. In addition, they shall participate in the formulation, implementation and evaluation of plans and programmes for national and regional development which may affect them directly.”

This “land defense” mentality isn´t so much a proclamation by the indigenous communities that “this land is ours”, but rather an affirmation that “this land is us”. It is in this subtle defense where we find that third option to violence. “This land is ours” would revert back to meager ownership and possession which is a conception of Western civilization and unknown to most pre-1492 Mayan Cultures. The struggle between “mine” and “yours” inevitably opens the door to conflict and violence. “This land is ours”, however, changes the paradigm. It makes sacred the land, the people on it, and the intricate web of relations that exist therein. It is this web of relations that is worthy to defend because it is who we are.

I think that this mentality is what needs to be nurtured in the barrios and marginalized neighborhoods of San Salvador. Instead of more police control or more “hard-hand” laws against delinquents; instead of an apathetic resignation to the reality of violence; instead of some un-rooted academic analysis of the causes of violence; these communities need to find ways to make sacred once again their streets and neighborhoods and parks. They need to take back those areas in their communities that have been kidnapped by violence and reconstruct a sense of community belonging teeming with trust and friendship and mutual caring.

My mother-in-law, Marina, is an underprivileged single mother working in a sweatshop for miserable wages. She lives in an underprivileged community distressed by rampant violence. But on New Year´s Eve last year, she demonstrated how violent urban areas can find ways to once again revere their local communities. Marina organized a party to celebrate the New Year with the local community. She raised funds to bring in a sound system and a DJ and at 10 PM on the 31st the party started. Though most families had, as usual, locked themselves behind the razor wire surrounding their houses at 8:00 PM, the music and lights gradually drew their interest. By midnight the streets which were usually given over to the gangs and drug dealers after 8:00 PM, were flooded with people of all ages dancing and laughing and celebrating the New Year. Women were cooking tacos and pupusas on the street corners without any fear of extortion, because the gang members that regularly extorted them were in the middle of the party dancing with the rest of the community. People, who usually shunned any and all contact with the “evil” gang members, were now sharing a plate of tacos and mutually enjoying the party.

It was a moment when the community became sacred again, when the fear associated with violence melted away and when the community collectively affirmed that this place is us—we are this place—and we will defend it from anything that threatens. It was a moment that offers, I think, a new and urgently needed response to the violence affecting Central America. And it was a moment when a community oppressed by violence recognized and brought to fruition the biblical promise that: “There should be no poor (or violence) among you, for in the land the LORD your God is giving you to possess as your inheritance, he will richly bless you.” Deuteronomy 15:4

Tobias Roberts does community development and advocacy work with the Mennonite Central Committee in Guatemala.

Sorry, comments are closed.