Who Determines Health? The Dangers of Nutrition Education

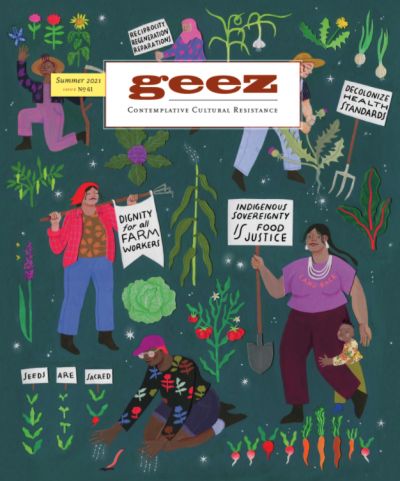

Image credit: Molly Costello (they/she), Detail of “Tending Just Food Futures,” April 2021, Cut Paper, Gouache, and Coloured Pencil on Watercolour Paper, 11 x 14 inches.

Historically and today, those who are in closest proximity to systemic power are the ones responsible for assigning value to food and ultimately deciding who is worthy of eating and who is not.

The audio is a transcript of the written piece recorded by Patrilie Hernandez for Geez Out Loud.

For the better part of my food justice career, I believed my role in the field was to increase access to healthy food in vulnerable communities. It started over a decade and a half ago after dropping out of a small liberal arts college and landing in the restaurant industry when I was encouraged to enrol in culinary school. There, I obtained a degree in hospitality management while simultaneously working full time in order to pursue what I thought was my dream of becoming a chef.

But life had other plans for me when I decided to volunteer for a non-profit organization that offered healthy cooking classes for adults, children, and families in my local community. By 2010, I was convinced I had finally found my calling: teaching kids how to make nutritious meals, coaching families on how to buy healthy food on a budget, and advocating to increase food access in high-poverty areas through farmers’ markets and grocery stores.

These goals seemed to align with the broader vision of the Food Justice Movement, which sprung out of the Civil Rights Era of the 1960s and the Environmental Justice Movement of the 1990s. Over the past three decades, the Food Justice Movement has evolved as health-focused government agencies, non-profit organizations, and advocacy groups have partnered to tackle food insecurity and increase access to nutritious foods in marginalized communities. While collaborative efforts from these stakeholders has brought visibility to these issues in public health spaces, it has also set up white supremacist and colonized narratives around nutrition education.

People might be tempted to think that nutrition experts are the ones who determine if food is “healthy” or “unhealthy” based on scientific studies. But objectively, food, at its most basic core, is neutral. It’s true that food is composed of macronutrients (sugars, fats, proteins) and micronutrients (vitamins and minerals) that contribute to our health and help us function in daily life. But it is equally true that the way we think of food is largely shaped by dominant systems of power. Beliefs around what food is considered “healthy” or “unhealthy,” “good” or “bad,” “clean” or “dirty” are defined by the norms and behaviours of society – and therefore social hierarchies. Historically and today, those who are in closest proximity to systemic power are the ones responsible for assigning value to food and ultimately deciding who is worthy of eating and who is not.

I’ve seen this power dynamic play out in my own life as a nutrition specialist. First, most of the non-profit organizations that I volunteered or worked for perpetuated the belief that neighbourhoods with concentrated areas of BIPOC people living in poverty are lacking or broken, and that we were there to “fix” their lives. I came to the realization that even as a multi-racial person of colour within the Puerto Rican diaspora, I chose to exploit my proximity to whiteness as a way to justify entering “underserved” or “under-resourced” communities.

The reality, however, is that I was a part of a rotating cast of outsiders with race and/or class difference who would show up at schools or local recreation centres, attempting to be in relationship with community members for a short period of time, only to move on when grant or program funding ceased. It took me a long time to come to terms with the fact that I could have been potentially causing more psychological violence and harm to these neighbourhoods than if I had never entered them in the first place. Not only that, but I was also projecting my body beliefs and food behaviours (which would later be diagnosed as an eating disorder) onto children and families that looked up to me because of my professional expertise and academic background.

These experiences were not unique to community-based non-profit settings; I would see this power dynamic in community health settings as well. I encountered numerous health and nutrition professionals with systemically dominant identities (thin, cis, white) that would dismiss a BIPOC patient’s cultural identity when offering nutrition counselling. For example, community health clinic staff would often demonize culturally necessary foods like white rice or tortillas in lieu of “healthier” alternatives. Interestingly enough, these alternatives had almost the exact same macronutrient profile as the original foods, but were only viewed as “healthier” because they came from a white American lens.

Ironically, the same professionals would suggest traditionally Indigenous foods (like quinoa, turmeric, or chia) under the guise of being “healthy,” without taking into account that these foods might not be accessible for many communities in the U.S. Furthermore, appropriating these foods and claiming them as the newest “superfood” often results in the commodification and exploitation of the labour and land where they originate. In this way, foods deemed “foreign” or “exotic” are simultaneously demonized and appropriated. This stems from underlying structures of white supremacy and colonization, and unfortunately still heavily informs the profession today.

In mainstream nutrition education, we are taught that “healthy” eating is “successful” if one’s body gets smaller or loses weight. Unsurprisingly, many of these programs are led and facilitated by white (or light-skinned) cis women, who have historically been the most indoctrinated by American Exceptionalist ideology – teaching them that a slender aesthetic was the ultimate sign of societal superiority. This body ideal is further promoted by metrics such as BMI (Body Mass Index), Western medical practices, and other health spaces. It is deeply rooted in white supremacy, anti-Black racism, and settler colonialism.

The message that being in a large body means that something that is “wrong” or “unhealthy” is predated by racist and misogynistic rhetoric going back well before the 16th century. Sabrina Strings, sociologist and author of the acclaimed book, Fearing the Black Body: the Racial Origins of Fat Phobia provides historical evidence that fear of fatness or “fatphobia” precedes the medical establishment’s concerns about excess weight by nearly 100 years.” This fear continues to vilify and oppress Black and Brown bodies, well after the peak of colonization and chattel slavery.

The evidence is abundant: nutrition education practices are steeped in white supremacy, systemic oppression, and colonialist ideology. Whether you consider yourself a nutrition educator or part of the food justice movement, it is imperative that we all examine harmful narratives around food choice and demonstrate a sincere commitment to dismantling inequitable food systems.

Patrilie Hernandez, MS (she/they) lives in Washington, D.C. She combines her academic background in anthropology, nutrition, and health, with her lived experience as a queer, fat, neuroatypical, multiracial femme of the Puerto Rican diaspora to disrupt the status quo of the local health and nutrition community.

Start the Discussion