Fundamentally divided?

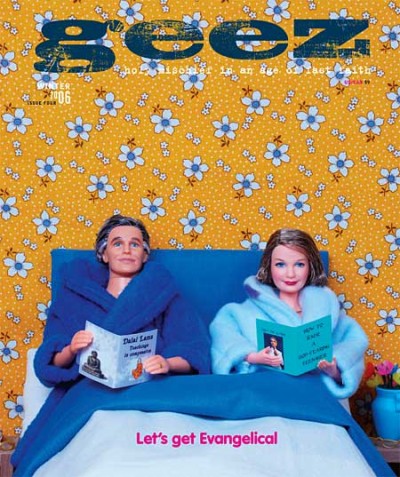

I’ve recently embarked on a new relationship. It’s with God. Actually, it’s with a member of God’s flock, a self-proclaimed “follower of Christ.” But for someone like me, a secular New York Jew descended from a godless mishmash of Zionists, Communists, and American western pioneers, this is meshugas enough.

“Sarah” is the sister-in-law of a friend of mine. She has agreed to embark on an ongoing email exchange designed to explore the question: is constructive conversation possible between evangelicals and secularists? More urgently, is conversation possible around the “hot-button” issues currently dis-Uniting the States? How do we engage in a dialogue – “an exchange of ideas and opinions,” according to Webster’s – that doesn’t end in the un-Christian behavior of one party punching out the other’s lights?

Sarah and I set out to conduct our own small-scale science experiment. We focus, at my request, on abortion. Since Roe v. Wade legalized abortion in 1973, strong language (“sin,” “murder,” “evil”) has flowered on both sides. One faction fights to save the million-plus “unborn children” aborted in the U.S. each year, while the other fights for the right of women and doctors to engage in a legal medical procedure free of the threat of harassment or murder. Despite the fact that women have historically turned to abortion as a last resort, regardless of its legality – and despite the fact that illegal abortions accounted for almost 20 percent of all deaths attributed to pregnancy and childbirth pre-Roe, according to the Guttmacher Institute – 18 states are poised to criminalize abortion should Roe be overturned. The storm surrounding abortion obscures and distracts from more pressing goals: reducing the poverty, ignorance, and lack of access to contraception and preventive health care services that contribute to abortions in the first place, for instance. Taking a stab at civil dialogue seems worth it when so much is at stake.

But even before Sarah and I even get into the issue, my hackles are rising. I’m busy polishing what my liberal rabbi friend calls my “stump rant” when it hits me: I really don’t know my audience. I have absolutely no contact, casual or otherwise, with fundamentalist Christians (in New York, of course, fundamentalist Jews are another matter). I have only stereotypes to go on: “fanatic,” “misogynist,” “bigot.” Sarah is in a similar situation; as a teacher at a Christian school, she “[doesn’t] get to talk with many people who are not Christians.” For all I know, she holds equally poisonous views of me and my ilk.

The thought of engaging in “constructive dialogue” with someone who quite possibly thinks I am going to hell is unnerving. Will we actually “discuss” anything, or will our virtual conversation devolve into mudslinging? I don’t relish the prospect. Nor, it turns out, does Sarah. “I don’t know if you have had an abortion and my words and point of view are very personal or painful for you,” she writes. “I hope I am not causing you to feel antagonistic towards me.” At least we’re both nervous. I feel an odd sense of kinship.

While neither of us wants a fight, it’s clear that when it comes to our most basic beliefs, Sarah and I are equally intractable. I do not believe, for example, that human life begins at the moment of conception. When I open the Good Book (and it’s not often), I see an allegory – not, as Sarah does, an account of “real people who led real lives, sins and all.” I do not believe premarital sex is wrong. I believe each woman is the best judge of her own readiness for parenthood. I consider adoption one of the most meaningful mitzvahs, but I don’t believe the availability of the option justifies forcing a woman or girl to give birth. And so on (and on and on).

Sarah’s beliefs are worlds away from mine, although to my surprise, she tells me that she has “not always been a follower of Christ. At one time, like you, I thought a woman had the right to choose an abortion.” But one day, Psalm 139:13 hit home (“He wove you in your mother’s womb”). “If a life is created in a mother,” she decided, “then He created it for a purpose and a reason.” The realization that “every life is precious to God and should not be terminated” was an “eye- opening thought for me,” Sarah says, one that “felt right. If God did not want a life started, He had the power to not start one.” (Interestingly, she considers birth control use a responsible behavior, although contraception or no, “God will start a life if it is His plan.”) She notes that while there are “many accounts of pregnancies that were from rape, incest, adultery – there is some unbelievably sinful behavior in the Bible – not once did anyone terminate a pregnancy,” and she cites “many mentions” in the Bible of “babies in the womb being active and alive.” We are blessed and cursed with free will, which allows us to “make choices that are pleasing to God or choices that are not pleasing to God.” His love notwithstanding, “we are all sinners” in the end.

Oh, boy. Now what?

Fortunately, each of us accepts (or seems to accept) the futility of winning over the other. “I am not trying or expecting to change your mind,” Sarah writes. “I hope that our dialogue can be open, honest, and for the purpose of gathering information.” Thou shalt inquire, not inculcate, our commandment might read. I am grateful to Sarah for making an effort at dispassion, and I vow to try and do the same. I think of a phrase coined by the Public Conversations Project: “listening with resilience,” even when what is said is hard to hear.

And it is hard. Fascinating, but hard. At times, our similarities seem to serve solely as reminders of our differences. For example, both Sarah and I know women who had abortions. Her friends “still struggle with the ‘choice’ that they made to end a pregnancy,” Sarah says. “At the time, each felt that they had ‘no choice’” (an interesting observation, given the stated desire of many evangelicals to restrict rather than expand women’s options for preventing pregnancy; clearly, a woman who feels she has “no choice” over her reproductive options suffers no matter which side of the issue she’s on). Could they revise history, Sarah’s friends may well have decided to carry their pregnancies to term. Contrast with my friend Anna. Given her lack of emotional and financial readiness when she got pregnant at age 17, she says, bringing a child into the world would have been unethical. Twenty years later, she still considers her abortion painful, scary, emotionally traumatic, and absolutely the morally right decision.

Sarah and I share another similarity: we are mothers. But whereas parenthood has strengthened my conviction that only a woman can judge whether she is capable of taking on the colossal, monumental undertaking of pregnancy, birth, and child-rearing, Sarah’s experience leads to different conclusions. One of her three children was conceived after birth control failed, and while “at first this was not a happy thing for my husband or myself,” she is profoundly thankful that she followed “God’s plan” and had the baby. She also legally adopted her stepdaughter, born of an earlier relationship of her husband’s. “[This daughter] is a gift of God,” she writes. “If her birth mother had had an abortion at age 14, I would not have this amazing young woman as my daughter.” Sarah’s commitment to her children moves me, and I find myself wishing that every pregnancy could result in such joy.

Given the combination of Sarah’s life experience and Biblical commitment, her views on abortion make absolute sense. “God has a plan and a purpose for all life,” she believes, even if “life does not always start in love… A baby is a life at the moment of conception. That life may not be convenient for the birth mother, but it is a life with a purpose. There are many people who would happily adopt… I understand that carrying a baby for nine months is an inconvenience, but I feel it is the responsibility of the birth mother.” Her choice of words startles me. In my experience, no woman or girl desperate enough to contemplate an abortion would relegate unintended pregnancy to an “inconvenience.”

Thinking about Sarah’s friends makes me shiver. I cannot imagine the torment endured by women who feel they should not have ended their pregnancies. Nor can I imagine the suffering endured by women who, because of legal, financial, or geographic lack of access to safe abortion, end up bearing children they cannot raise. Should the pain of the former group justify restrictions on the latter? “My heart truly and honestly aches for those who have chosen to terminate a pregnancy,” Sarah says. As for women considering abortion, “I would encourage them (with love, understanding and kindness) to choose to give birth to the child and to give the child the gift of adoptive parents, or to raise the child.” Sarah’s desire to do right is heartfelt and honorable. So, for that matter, is mine. If our divergent personal experiences are any evidence, doesn’t “doing right” take many forms? Raising an unplanned child might salvage one life, while terminating a pregnancy might salvage another. Legislation that mandates Sarah’s decision while criminalizing Anna’s disregards the truth: far from being an either/or situation, all women confronting unintended pregnancy make a profound ethical decision regarding the care of a child. Particularly since it will inevitably and disproportionately affect poor women, such legislation seems more than uncharitable. It seems downright un-Christian.

Sarah disagrees. As she and I continue to communicate online, I find myself wondering: which of us will break the rules and unleash our sermon first? I’m afraid it might be her. I’m even more afraid it might be me, preaching my gospel of fact: “Are you aware that the Federal Abortion Ban provides no health exemption for mother or fetus? That 98 percent of Planned Parenthood funding goes toward preventive health care services, not abortions? That the ‘morning-after pill’ prevents pregnancy but has no effect on established pregnancies?”

It helps to remember the words of AIDS activist and educator Matthew Denckla. “Frankly,” he says, “I think it’s important that the ‘culture wars’ of the last two decades be reframed as a war against constructive dialogue and toward a rampaging, ugly partisanship that is demeaning, full of personal attacks, and sweepingly simplistic.” We’re all losing here. In this environment, civility might be the stealth weapon that, skirmish by skirmish and conversation by conversation, wins the war.

Juliet Eastland’s writing can be found in Bitch, Orion, AlterNet, and other print and online publications.

Sorry, comments are closed.