A Different Kind of Mennonite

Credit: Robert Burdock, https://flic.kr/p/adLmH8

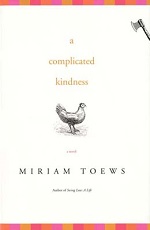

Nomi Nickel, a teenage girl living in a small religious village known as a tourist attraction, is the heartwarming and ironic protagonist in a novel that entwines memory, personal experience and culture. Her story is a beautifully written mosaic by Miriam Toews (perhaps you’ve heard of her), a Canadian writer, who is profoundly peeling back the layers of what it means to be raised in an environment where religion dominates and freedom eludes in her 2004 national best-seller, A Complicated Kindness.

Nomi Nickel, a teenage girl living in a small religious village known as a tourist attraction, is the heartwarming and ironic protagonist in a novel that entwines memory, personal experience and culture. Her story is a beautifully written mosaic by Miriam Toews (perhaps you’ve heard of her), a Canadian writer, who is profoundly peeling back the layers of what it means to be raised in an environment where religion dominates and freedom eludes in her 2004 national best-seller, A Complicated Kindness.

From very early on we are told what being Mennonite is like. “Five hundred years ago in Europe a man named Menno Simons set off to do his own peculiar religious thing…” This is just one example of several transgressional statements where Nomi half-jokingly jabs at the early stages of Mennonite tradition. In a passage dripping with sarcasm, she recites, “During the war all the French men had to go off to fight, but the Mennonites didn’t because Mennonites are conscientious objectors (man, can they object), and so while the French guys were off fighting in Europe, the Mennonites went and bought up a lot of their farmland really cheap from the women left behind who were desperate for money…” When she presents this to her teacher as an assignment it is deemed “irrelevant”. The impression this has on the reader is that not only is her version of Mennonite history rejected, but also, since she discovers this on a bike ride to a neighboring village, her overall self-journey.

Soon after, Nomi offers the following gem which sets up the crucible of the novel while also revealing the incredible ingenuity of her character, she states, “I wonder what exactly happened in Menno’s world that made him turn his back on it.” Rejected by the social standards of her own community, Nomi finds herself on the outside looking in, creating an interesting bridge between herself and her Mennonite ancestors. Nomi is very much a Mennonite, yes, but she is a different kind of Mennonite.

There is much to unpack and Toews does an excellent job doing it without overdoing it. She gives us glimpses. She offers us short stories that contain a great deal of wit and humor. Music from a classic rock era score several memorable scenes. Toews energy is contagious and her ability to craft poignant prose without coming across as pedantic is on fleek.

So what does it mean to be Mennonite? Who gets to say? Why?

In the novel, the answers come from an uncle figure simply known as “The Mouth” who represents the height of fascist fundamentalism. He is malicious to the point that it is somewhat easy to understand where the criticism of the novel generates. As the authority figure of ideal Mennonite belief, The Mouth is a fear mongering overlord and I wonder if Toews is putting forth a version of Mennonite upbringing that has little to do with actual Mennonite practice (or is exaggerated in some way) and is protesting the narrow minded expression of faith depicted in her novel. The character certainly serves the literary purpose of being the villain. What remains is that Toews has written one of the best survival stories in modern Mennonite literature.

A Complicated Kindness removes the meek and non-violent mask of several generations of unquestioned religious/political history in which fundamentalism acting under the guise of kindness has been all too common place. The go to opinion of popular thought is ready to believe this portrayal of the reclusive, uptight community which needs to lighten up from its dogmatic ways, thus, contrasting this sort of environment with a free spirited whimsical young girl whose primary concern is to be with her family and hangout with the rock musicians she admires (who doesn’t enjoy the musical styling of Neil Young?) makes the character of Nomi Nickel easy to imagine and hard to forget.

Miriam Toews accomplishes all this without being mean spirited and I am ultimately left stunned by her story. I suppose, to not view the novel as an undermining of religion of old is to not hear the voice of Nomi breaking softly under its weight. With great sensitivity, rethinking and re-imagining, Toews has cut beneath the surface of popular themes (adolescence, romance, coming of age) and emerged with a story that shapes and redefines ‘Mennonite’ all together. Instead of Menno Simons having the last word, this one belongs to Nomi from East Village.

Sorry, comments are closed.