More Like a Mechanical Jerk

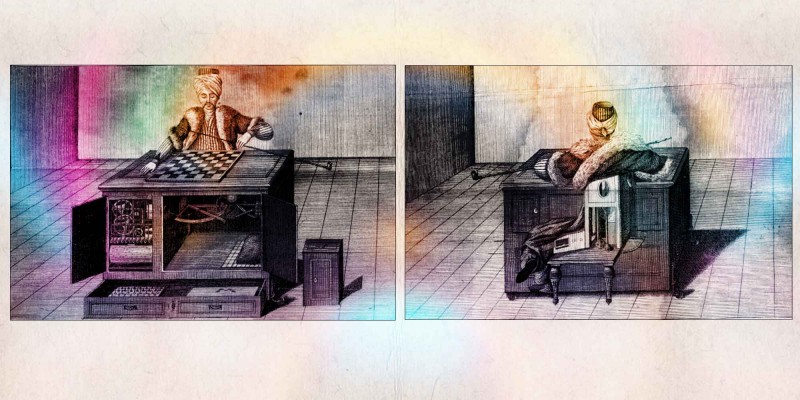

The Mechanical Turk from Karl Gottlieb von Windisch’s 1784 book “Inanimate Reason”

In 1770, Wolfgang Von Kemplen, a brilliant inventor and member of Holy Roman Empress Maria Theresa’s court, brought his newest technological marvel, the Mechanical Turk, to amuse and astound the Habsburg royalty. Von Kemplen constructed a clockwork robot, or automaton, that could play chess and best many of the chess masters of Europe. In its 85-year career, the automaton came into contact with many historical figures like Benjamin Franklin, Napoleon Bonaparte, Catharine the Great, and Edgar Allen Poe.

Von Kemplen’s creation consisted of two major set pieces. The first was a large wooden cabinet hosting a chessboard. Within the cabinet were densely packed gears and cogs which would spin, whirl, and click. The second was a man carved out of wood wearing a robe and turban in the style of a Turkish magician. Together, the gears would move the wooden man and allow him to move chess pieces around the board. Von Kemplen would then invite a member of the audience to play a game of chess against his automaton. In a seemingly miraculous show of technological ingenuity, the automaton would nearly always win.

But the Mechanical Turk had a secret which remained unknown to the audience: within its cabinet was an elaborate compartment for a human to control the movements of the automaton. Many came close to discovering how the machine truly worked, the writer Edgar Allen Poe being one who got particularly close to being right. In 2024, this seems obvious and silly. Of course, a clockwork robot from 1770 couldn’t beat a human at chess. After all, it wasn’t until 1997 that IBM’s chess-playing AI, Deep Blue, would beat world chess champion Garry Kasparov.

Our modern feeling of superiority is unfounded because we still share in the same astonishment as those gawking at the Mechanical Turk. Like the Mechanical Turk concealed the labor and genius of a real human chess player, technology like AI conceals the real human labor necessary for it to work. When it comes to technology, our beliefs about it far surpass what it can actually do.

AI platforms give us a similar feeling of amazement. We live in a time when AI can summarize a book, write poetry, create art (sort of), and more. But because capitalism obfuscates the production of commodities through a fancy sleight of hand called “commodity fetishism,” the human labor on which AI relies goes unrecognized. Throughout the Global South, workers in countries like Colombia, Venezuela, Kenya, India, and the Philippines perform “microtasks” for data companies to train the AI. In a harrowing twist of irony, Amazon’s microtask platform is called “Mechanical Turk.”

Pay for these microtasks ranges from two cents to 50 cents per task, resulting in around one U.S. dollar for an hour of work. While the pay is meager, the irregular pattern of work makes life increasingly difficult for workers doing these jobs. Sometimes, there’s not enough work to fill an entire week, making finding additional income a priority.

The people of Von Kemplen’s time are not fundamentally different from us. They didn’t believe in the Mechanical Turk because they were unsophisticated or dupes, but because they, like us, believed in a frictionless world where science and technology could handle all of our problems. Like us, they also often didn’t recognize or couldn’t imagine how it all worked. No matter how magical it appears, technology relies on real and exploited human labor. When it comes to understanding our technological world better, we ought to follow in the footsteps of those who tried their hardest to understand the magic of the Mechanical Turk. Like Edgar Allen Poe and other investigators of the Mechanical Turk, we must become detectives of technology and look for where our human and nonhuman siblings are being exploited.

Matt Bernico is a labor activist and writes on topics pertaining to religion, social justice, and climate change. You can hear more from Matt on his weekly podcast, The Magnificast.

Start the Discussion