ChatGPT Spirituality: Connection or Correction?

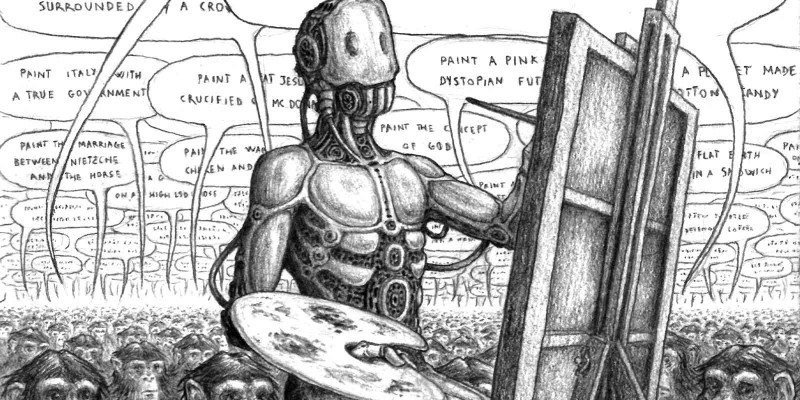

Detail of “The Age of AI Art,” Davide Edoardo Cassano, 2023, graphite on paper, 21 x 14.5 centimetres

Earlier this year, I was at an academic conference sitting with friends at a table. This was around the time that OpenAI technology – specifically ChatGPT – was beginning to make waves in the classroom. Everyone was wondering how to adapt to the new technology. Even at that early point, differentiated viewpoints ranged from incorporation (“we can teach students to use it well as part of the curriculum of the future”) to outright resistance (“I am going back to oral exams and blue book written in-class tests”).

During the conversation, a very intelligent friend casually remarked that she recently began using ChatGPT for therapy – not emergency therapeutic intervention, but more like life coaching and as a sounding board for vocational discernment. Because we all respected her sincerity and intellect, several of us (including me) suppressed our immediate shock and listened as she laid out a very compelling case for ChatGPT as a therapy supplement – and perhaps, in the case of those who cannot or choose not to afford sessions with a human therapist, a therapy substitute. ChapGPT is free (assuming one has internet), available 24/7, shapeable to one’s own interests over time, (presumably) confidential, etc…

In my teaching on AI and technology throughout the last semester, I used this example with theology students (some of whom are also receiving licensure as therapists) as a way of pressing them to examine their own assumptions about AI – and then, by extension, their own assumptions about ontology. If the gut-level reaction to ChatGPT therapy is that it is not “real,” then – in Matrix-esque fashion – we are called to ask how we should define “real.” If a person has genuine insights or intense spiritual experiences engaging in vocational discernment with a technology that can instantaneously generate increasingly relevant responses to prompts, then what is the locus of reality that is missing?

Some insights emerge when we think about how our spiritual traditions (in my case, Christian theology) have sought to describe genuine connection. Many of the more affective terms (e.g. feeling understood, feeling synchronicity between two entities, etc.) are, I would suggest, increasingly plausible through connection with AI. In other words, if “real” connection comes from feeling truly connected, then there is no reason to think that AI technologies will not be able to replicate and perhaps even surpass person-to-person connection on that front in the near future. However, Christian theology has also described genuine human interaction, not simply as feelings of connection, but the experience of correction – specifically, the realization that the Other with whom I am engaged is not simply a screen on which to project my own desires (Feuerbach-style), but a genuinely different consciousness than my own, one that is not plastic or shapeable to my own desires. One that can push back, one that can free us from the prisons of our own minds – especially when we do not recognize our subtle and not-so-subtle twisting of external realities for our internal desires.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer, in his masterful book on Christian community Life Together, argued (in a manner surprising for a German Lutheran of his time) for the restoration of individual confession and absolution among Protestants for precisely this reason. He pointed out that, if I am only making confession to God in the solitude of private prayer, it would be easy to shape God into a self-serving idea for my own justification. However, the presence of another human being as confessor forces me to engage that which – unlike the idea of God – resists my subtle twists into idolatry, namely, the flesh and blood human other. For Bonhoeffer, the reality of God is iconically present in the reality of the human other.

Theological conversations around AI will necessarily evolve as the technology does. But we would be wise to make sure that talk of genuine connection incorporates insight around the blessedly “hard” facticity of the human Other as its own gift of freeing ourselves from ourselves.

Robert Saler is Associate Professor of Theology and Culture at Christian Theological Seminary in Indianapolis, Indiana.

Start the Discussion