Guest Ethics

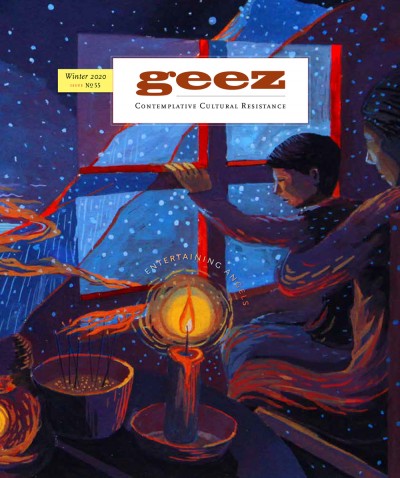

I Remember Happiness Credit: Jess X. Snow (details below)

For the last year, I have lived as a guest. Here’s what I’ve learned so far.

^John Bergen reads his piece as part of Geez Out Loud. The audio is an exact reading of the written article.

Since I graduated college last May and taken that so-called next step into “adulthood” (whatever that is), I have lived as a guest in other people’s spaces.

I work for Christian Peacemaker Teams, meaning that I spend much of my time living in the hospitality of local communities who directly face state violence and occupation (Palestine) and the violence of extractive industries and non-state militias (both Palestine and Iraqi Kurdistan). On my time off I’m on friends’ couches in the States – last year my parents moved out of their home to go work in Ghana. I have no home to return to. None of these places are “mine” and in a lot of ways, none of them are “home.”

And I’ve learned from it. Learning how to be a “good guest,” an ethical guest, the kind who is invited back, has taught me a lot about power, culture, and history.

First off, I should clarify that “guest” can mean a lot of things. Catholic Worker communities and other radical groups frequently talk about “guests” as a way of shifting away from a neoliberal social services model of “clients” receiving “services” to a model of beloved community and interdependence. Catholic Workers recognize that everyone can contribute to the “hospitableness” of a space, and most intentional communities have explicit processes for how “guests” can become permanent members of the community.

On the other end, the massive “hospitality industry” maintains a very clear line between exploited “hospitality workers” who provide services for wealthy “guests” whose every need is met. The homeless woman at the shelter is a “guest;” as is the slumlord real estate magnate staying at the five-star hotel.

On that spectrum, I fall more towards the second type of guest. I graduated from an elite liberal arts college, my parents have college degrees, I am able to work for a scrappy international human rights organization because my family helps with my student loans, and the friends who host me when I am back in the States live in generally nice neighbourhoods, safe from violence (both police and local community violence).

But wherever a “guest” sits on the spectrum, we sit in a place of dependency. We are reliant on the labour of others who offer us hospitality. Three things on this: the impossibility of exchange, the act of receiving hospitality, and listening for cultural difference.

When I am a guest in someone else’s space, I often catch myself trying to overcome my dependency, to make hospitality an exchange of services. I’ll offer to do the dishes, cook food, clean the house, buy food, play with the kids, do your laundry . . . there can be a certain desperation in it. I struggle to accept others taking care of me. I find myself wanting to make this relationship, one based on care, into a relationship based on (capitalist) exchange.

The tourism industry tries to make this exchange model of hospitality feel normal and satisfying, like I’ve justified myself in receiving care because I’ve paid for it. However, the feeling of “equal exchange” that I get at a hotel (I give a hotel money and they take some of that money to pay people to clean my hotel room and make me coffee) is a lie for two reasons: 1) The money goes primarily to the owner of the company and not those actually providing hospitality, and 2) The primary offer of hospitality is shelter from the storm, which is not something that can be immediately exchanged. I can cook all the food in the house and it isn’t the same as someone opening up their home to me. There is something else – an offering, a recognition of need – that cannot be reduced to money. Hospitality isn’t exchanged, it is given and received.

While I can’t exchange services with my host, there are things that I can do, and the first is to actively and openly receive hospitality. So many of our religious texts and traditions make hospitality a central imperative and name guests as incarnations of the Divine. To be a guest then, is to offer someone else the chance to fulfill their divine duty, to welcome the sacred in me as I bless the sacred in them. When I am a guest, I try to validate my hosts as good hosts, as fulfilling the divine command to open doors to those in need.

Finally, listening. Hospitality often has complicated rules based on our cultures and traditions. Being a guest means different things in different places. I noticed a big difference in how I was expected to behave as a guest in the United States as compared to Iraqi Kurdistan. In the U.S. and other places, one goal of hospitality is to make the guest feel “at home” – “here is the key to the front door, there’s beer in the fridge, the coffee supplies are in the cupboard on the left.” When I stayed with people in a Christian anarchist community in California, they told me that they felt validated as good hosts when one day I walked over their couch with my shoes on to answer the phone. I had made it my home.

Such behaviour would be horribly rude in Kurdistan where hospitality aims to provide for a visitor’s every need. My friend Latif would never tell me where the coffeemaker is and then say I can make it for myself. Guests must listen to their hosts to learn how to be good guests, the position cannot be taken for granted.

I think there is a lot we can learn from practicing being good guests. Neoliberal capitalism makes us perpetual guests: it uproots us, asks us to shift jobs and cities and communities. Flexibility and mobility are the future, contrasted with those barred from participating in capitalism: prisoners and imprisoned nations like Palestine. Many of us are long-term guests in North America as settlers who live on stolen land. My father’s family fled Russia during the Revolution and was offered land by the Canadian and U.S. governments, the traditional homeland of the Cree and Saulteaux nations. When we talk about justice for immigrants, we often talk about “offering hospitality.” What would it mean for us to act, not as arrogant hosts, but as the guests we are?

When it comes to the need for redistribution and reparations, we as white settlers are in need of offering something in return for several hundred years of being bad guests. As I’ve said, exchange isn’t really possible in hospitality. But listening to our hosts is. Learning how to act as good guests on someone else’s land, listening to the needs and demands of the places that we make “home” (however temporary) – these are things we must do. We do not have much longer to learn; already it seems as if the Earth itself is trying to evict us, driving us out of California and other places. We, as white settlers, as U.S. citizens, and ultimately as humans, must learn how to live as good guests before we are permanently shown the door.

John Bergen serves as the associate pastor at Germantown Mennonite Church in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He also organizes with Earth Quaker Action Team, a campaign to create solar jobs and a livable future in the Philadelphia region, and the Coalition to Abolish Death By Incarceration, a statewide campaign to end life-without-parole prison sentences.

This piece was first printed on Radicaldiscipleship.net in May 2015.

Images credit: Jess X. Snow, “I Remember Happiness,” December 2014, Digital Giclee Print of an original gouache on paper, 12”x6”.

Start the Discussion