The Cognitive Dissonance of Southern Hospitality

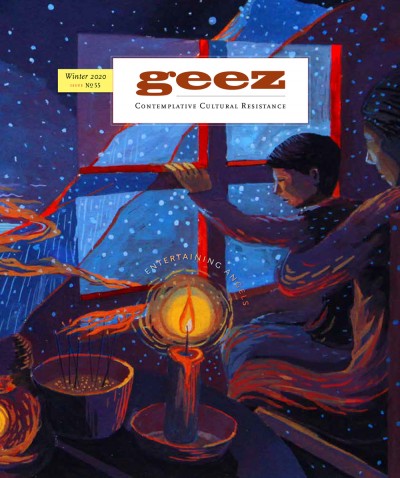

Old Age Security Credit: Jeff M for Short

Joe Marlon Lee had the same philosophy for his kitchen table as he did for his onion patch, as he did for his pond and pocketbook – what is it all for if not to be shared?

He passed that worldview down to my mother, and together with my father, she has maintained an open-backdoor, open-pantry policy for all of my life. My friends, throughout college and young adulthood and now parenthood, found a sense of place just as I found a sense of place on that piece of Louisiana acreage. An insult it almost was for someone not to make our home their home throughout my upbringing. This sentiment echoed throughout my childhood town’s pharmacy, and football stadium, and the sanctuary in which I was pruned for a world much different than the one responsible for my raising.

I am crying as I reflect on Southern hospitality. It has shaped my entire life.

Always chilled teas (sweet and unsweet) sit in countless refrigerators as I type, just waiting on a guest to stop by. That subtle raise of the pointer finger from the steering wheel to the sky when passing a neighbour . . . a mail person . . . a stranger . . . is normalized throughout the towns. Don’t you dare think about getting sick and not having a parade of casseroles and pound cakes dropped off on your doorstep – it’s not happening. Not here in this humid, holy, horrific-history-packed hemisphere that is the Deep South.

They call it cognitive dissonance, right? This condition of so loving and loathing, committing to and criticizing a person, place, or system. I have this here. In my southern home, I mean. My husband and I have been asked numerous times, based on our progressive ideology and theology, why we just don’t leave. Wouldn’t it be easier elsewhere? Some place more homogenous, less resistant? Some place that isn’t as proud of its plantations or hell-bent on its policies?

I don’t know that it would be easier, because it would not be home. So we stay, and we hold in tension our quickly changing minds and our slowly changing environments.

And we live ever surrounded by the competing realities of southern hospitality and the inhospitable “isms” of our region. Having worked for multiple Louisiana churches and lived in an intentional community for years in this area, I have experienced what has seemed like the best and worst of openness. From unlocked back doors and “make yourself at home!” to the sting of church-influenced homophobia, from incredible responses regarding hurricanes to racism guised as missions, the South contains multitudes. Of it, I am proud and embarrassed, which I guess means that I contain multitudes as well.

Extreme darkness and incredible light coexist here, as I suspect it does in other places. To deny either is to deny a reality that seems of utmost importance if we’re going to get anywhere together. Southern people and communities have a magnificent capacity for welcome, and a deeply imbedded disease of oppression coursing through its piney woods. It is both, and. From it, I have learned more warmth and generosity than I have seen in most parts the globe over. And from it, I have learned the idolization of religious-backed power alongside the camouflaging of said power until it is unrecognizable even to the one who holds it. What a cross section of humanity, this being drenched in trauma and the image of God.

But this tension, while uncomfortable, only means that we’re being honest. And the staying, while tiring, only means that the reform of a place that comes uniquely by way of those who so deeply love it has potential. This corner of the earth possesses something special to offer the stranger regarding radical welcome, if only it can continue to be further channeled toward the most marginalized among us.

Britney Winn Lee maintains equal levels of inner joy and ethical conflict in Shreveport, Louisiana where she writes books.

Image credit: December 29, 2006, “Old Age Security,” Jeff M for Short CC, flickr.com/tigerzeye.

Start the Discussion