Marilynne Robinson’s grace abolishes boundaries

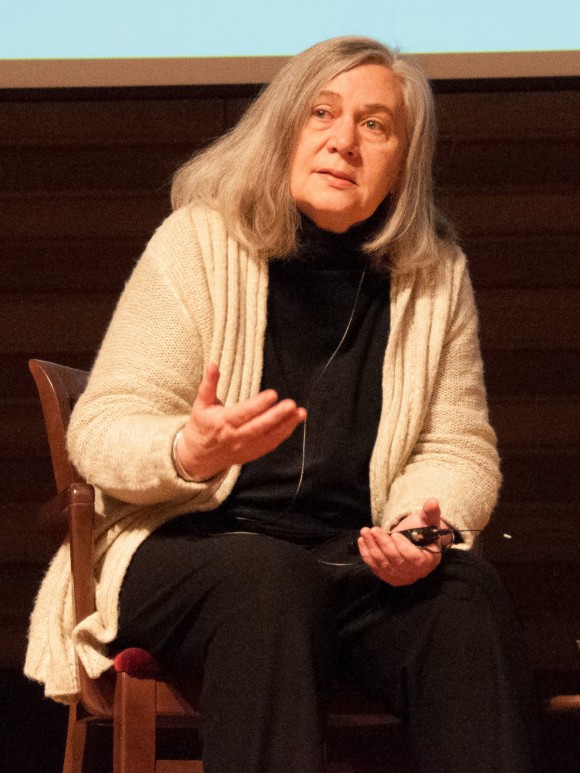

Marilynne Robinson, 2012 Festival of Faith and Writing, Calvin College. Credit: Christian Scott Heinen Bell, CC

I have a conflicted relationship with religious faith. I grew up Christian, but as often happens to people raised with religion, as I grew older I began to see the holes, inconsistencies and prejudice in the religious framework.

Still, whenever Christianity seems small and mean, I have only to crack open one of Marilynne Robinson’s novels to find a theology that is large, generous, and open-handed.

A week ago, I ventured into a church sanctuary to hear Robinson speak. She was in Winnipeg to deliver a sermon and a public lecture at St. Margaret’s Anglican Church. The American author whose 2004 novel Gilead won the Pulitzer Prize and who was recently interviewed – yes, interviewed – by the president of the United States, isn’t exactly easy to recruit for an event.

The organizing committee at St. Margaret’s worked for three years to bring her to Winnipeg. But anyone familiar with Robinson’s body of work – four novels, a book of journalism and four essay collections – won’t be surprised to hear she accepted an invitation from a church. Her theology propels everything she writes, either overtly or flowing just under the surface.

I came to church that night, not to hear a sermon per se, but to listen to someone whose writings I treasure almost like sacred texts. Robinson’s novels make me weep. When I reach the last page, I usually turn the book over and start again at the beginning. What touches me so deeply in Robinson’s fiction is her compassion for her characters, her grace. Here is a woman who sees every human being, no matter how small-minded or desperate, as imbued with the radiance of God.

The Sunday evening service was crowded; our body heat warmed the chilly sanctuary. (The church’s boiler was broken.) As I waited for the service to begin, tugging my sweater sleeves over my wrists, I struck up a conversation with my pew-mate, Mark Golden, a retired professor of classics at the University of Winnipeg. He too had been smitten by Robinson’s prose. He described her first novel, Housekeeping, as “a masterpiece, a book which makes the banal marvelous and the spectacular normal.”

Golden stood respectfully during the hymns and listened attentively to Robinson’s sermon – a reflection that roamed from the Psalms to photons to micro-organisms to worship and its ability to awaken us to the sacred in the mundane. “We go through the day as if there was no miracle about the fact that we are walking in starlight,” she said. An unhurried, grey-haired woman in a woolen sweater, she diminished the pomp of the ornate and elevated oaken pulpit while exalting the work of bacteria.

Golden slipped out just before the Eucharist. Later I asked him what he thought about the service and he replied that while he loves Robinson’s writing and sympathizes with her tradition, he wasn’t persuaded by her words about worship. “I was raised in a secular household and have never had a question for which religion gave me a plausible answer,” he said.

Part of me agrees with him. I too stood silent during the reading of the creeds; I couldn’t repeat those words with conviction. Still, I was eager to accept the bread and wine the priest held out during the Eucharist. Something in that ritual speaks to me on the level of the mysterious. When the priest broke the bread and said “we are all of one body,” I accepted the elements as a sign of the unity and interdependence of all human beings, indeed all non-human life as well.

Religion troubles me the most when it is preoccupied with drawing lines between who is in and who is out. But in Robinson’s writing I find a far-reaching grace that abolishes any such boundaries.

In her novel Lila, we meet a homeless woman, abandoned as a child, drifting from town to town during the Great Depression. Lila falls into a relationship with an aging minister (the protagonist of Gilead) and we observe a dance of trust and distrust between two lonely people. Lila is drawn to the preacher’s compassion but suspicious of his religion that would cast her and the people she loves outside God’s embrace.

But Lila herself embodies a larger grace. She comes across a teenage fugitive hiding in a shack who confesses to murdering his abusive father with a piece of firewood. “Kindness was something he didn’t even know he wanted,” Lila thinks. She gives him her coat to sleep under and walks home, bare-armed in the winter wind.

“All good prose comes out of good perception,” Robinson said during her sermon. “It’s an extraordinary discipline, seeing, being alive to what there is to be alive to. This loving attentiveness is a God-like trait in human beings when they find their way to it.”

It’s Robinson’s acute perception combined with her unstinting grace that stretch the boundaries of my own acceptance and provoke me to look for the spark of the divine in every person, in every bacterium. If this is Christianity, count me in.

Josiah Neufeld is a writer and frequent contributor to Geez magazine. He lives in Winnipeg, Manitoba.

Sorry, comments are closed.