Indigenous Resistance Lifts the Veil of Colonial Amnesia

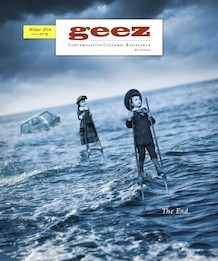

Robert Spence and Lionel Flett fishing on Split Lake. Credit: Matthew Sawatzky (link below)

It’s always been interesting to me when settlers talk about apocalypse. It reveals a kind of privilege and naïveté that is indicative of how complete the destruction of Indigenous peoples and our nations is in the mindset of most Canadians and Americans.

It seems strange to me that ideas of invasion, attack, occupation, and dispossession are recent fodder for television series such as The Walking Dead. This fictional reality is so strikingly close to the colonial legacy I was born into, at least in concept, it is sometimes difficult to see it as entertainment.

I know that people who have not lived through colonization, colonialism, and ongoing settler colonialism cannot begin to imagine the damage and the trauma it has caused both historically and in contemporary times. Nor can they begin to imagine how to attempt to live fulfilling, beautiful, and enriched lives in spite of being both occupied and dispossessed. This is the reality Indigenous peoples are faced with every day in North America, but it wasn’t always like this and our future together certainly does not have to be.

My Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg homeland is on the north shore of Lake Ontario. My elder, Doug Williams, from Curve Lake First Nation tells me that two hundred years ago, Lake Ontario had its own resident population of salmon that migrated all the way up to Stoney Lake to spawn. We drank directly from the lake and that was a good, healthy thing to do. There was a large population of eels that also migrated to Stoney Lake each year from the Atlantic Ocean. There was an ancient old-growth forest of white pine that stretched from Curve Lake down to the shore of Lake Ontario, that had virtually no understory except for a bed of pine needles. There were tall grass prairies and black oak savannahs where Peterborough stands today and on the south shore of Rice Lake or Pimadashkodeyong. Pimadash means “going across” and it refers to fire moving across the prairie beside the lake. The lake was teeming with manomiin or wild rice. The land was dotted with sugar bushes, the lakes were full of fish. It sounds idyllic, because it was idyllic. And the knowledge systems, the education systems, the economic systems, the political systems of Indigenous peoples were designed to promote more life. We were not capitalists. Capitalism is not an Indigenous concept. Our way of living was designed to generate life, not just human life, but the life of all living things.

Over the past two centuries, without our permission and without our consent, we have been systematically removed and disposed from most of our territory. We have watched as our homeland has been stolen, clearcut, subdivided, and sold to settlers from Europe and later cottagers from Toronto. We no longer have salmon in our territory. We no longer have eels or salmon in our territory. We no longer have old-growth white pine forests in our territory. Our rice beds were nearly destroyed. All but one tiny piece of prairie in Alderville has been destroyed. Ninety percent of our sugar bushes are under private non-Native ownership.

Our most sacred places have been made into provincial parks for tourists with concrete buildings over our teaching rocks. Our burial grounds have cottages built on top of them. The veins of our Mother have lift locks blocking them. The shores of every one of our lakes and rivers is lined with cottages or homes, making it nearly impossible for us to launch a canoe. Our rice beds have been nearly destroyed by raised water levels from the Trent Severn waterway, boat traffic, and sewage from cottages. The Haudenosuanee, Cree, Nishnaabeg, and Métis have all of Ontario’s industry within our territory and all of Ontario’s urban population.

Our children have been stolen from us and sent to residential schools, day schools, child welfare, and now into an education system that refuses to acknowledge our culture, our knowledge, our histories, and Indigenous experience. And then of course there is the Indian Act, which until the 1950s made our ceremonies illegal, made it illegal for us to hire a lawyer, made it illegal for us to leave the res without the permission of the Indian agent, and made it illegal for us to organize. The Indian Act still controls virtually every decision and every aspect of life from birth to the grave. It is a continuous system of control over Indigenous Peoples.

Which brings us to 1923, when the Williams Treaty was signed and the crown dishonourably took away our hunting and treaty rights, a direct attack on our ability to feed ourselves. My grandmother grew up eating squirrel and groundhog because if her parents were caught hunting deer or fishing they would be criminalized.

This is how my Ancestors, my family, and my relations have experienced settler colonialism.

It looks a lot like an apocalypse to me.

And it didn’t have to be this way; it doesn’t have to be this way. Settler colonialism and its system of domination is nothing more than a series of systemic choices upheld by collective choices, composed of individual choices. My Ancestors spent a great deal of time and effort trying to influence the outcome of our contact and our decision to allow settlers to live co-operatively on our land. They spent a great deal of time and effort in the late 1700s and early 1800s negotiating treaties with settler governments to ensure that our relationship to our homeland was intact and that their grandchildren and great-grandchildren could live our way of life in our homeland, unharrassed. Our diplomats and spiritual leaders articulated a way of sharing land that respected separate jurisdictions and our nation’s self-determination and sovereignty. It was our intention to continue to govern ourselves according to our own political traditions and to live in our territory in a close and intimate way with our first mother, the earth.

My Ancestors wanted the same thing that I want for the coming generations. I want my great-grandchildren to be able to fall in love with every piece of our territory. I want their bodies to carry with them every story, every song, every piece of poetry hidden in our Nishnaabe language. I want them to be able to dance through their lives with joy. I want them to live without fear because they know respect, because they know in their bones what respect feels like. I want them to live without fear because they have a pristine environment with clean waterways that will provide them with the physical and emotional sustenance to uphold their responsibilities to the land, their families, their communities, and their nations. I want them to be valued, heard, and cherished by our communities and by Canada no matter their skin colour, their physical and mental abilities, their sexual orientation or their gender orientation.

In many ways, four centuries of Indigenous resistance and mobilization on Turtle Island has been aimed at bringing about a decolonizing apocalypse – one that lifts the veil of colonial amnesia, amplifies Indigenous truths, and reveals the real and symbolic violence of settler colonialism. Indigenous resurgence movements are not just concerned with dismantling settler colonialism and ending the world, but also with bringing forth new realities based upon our ancient teachings and ways of being in the world. Apocalypse, the end of settler colonial oppression, the end of our abusive relationship with the Canadian state, and a radical decolonial transformation, means it’s the end of the world as we know it, and I feel fine.

Leanne Betasamosake Simpson is an author, activist, editor, and spoken-word artist. She is of Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg ancestry and a member of Alderville First Nation. Simpson is the author of Dancing on Our Turtle’s Back, Islands of Decolonial Love, and The Gift is in the Making.

Dear reader, we welcome your response to this article or anything else you read in Geez magazine. Write to the Editor, Geez Magazine, 400 Edmonton Street, Winnipeg, Manitoba, R3B 2M2. Alternately, you can connect with us via social media through Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram.

Image: Matthew Sawatzky, Split Lake Fishing

Sorry, comments are closed.