My best friend is a nice Gaia

Mothers, you have a hundred forms and a thousand growths. You who have a hundred ways of working, make this person whole for me. – Rig Veda

I know I belong to the earth, but I’ve forgotten how to live with her. Once I chewed bark and made muddy shelters. I knew which plants would heal and which would poison. In the Rig Veda, the hymn to the healing plants, medicinal plants are referred to as mothers because they sustain us. I want to draw close to this sustaining force, to be made whole by her wisdom. I long for an Eden of kinship, for a language for what I feel I should know but have no teaching of, for a consciousness connecting us. To welcome a raising of consciousness is to be pierced – to be interrupted – to be struck off the horse and turned around – to awake and look with new eyes, baptized. I want this piercing.

Going back to nature means sitting for a few therapy sessions to work on our trust issues with wilderness. We seldom welcome wilderness around us and seldom welcome wilderness within us. But don’t let three piece suits and tea cups deceive you, we are wild inside. How do we learn to trust the wildness of the wilderness and come to celebrate the wilderness within us? How do we welcome and raise a consciousness of interconnectedness?

I sometimes feel that we suffer daily betrayals every time we touch something improved upon. Once, I sat alone in my bedroom, kneeling before my bedroom door, weeping. I saw in the wood of the door an organic echo, the rings of the tree that made it. The door was not a door but a live thing, ripped out, cut down, and tailored for my purpose. And I wanted not to be guilty. I wanted to know another way. The heaviness I felt, palm pressed to the wood, was not something outside of me, something other people do, it was me. I’m afraid of my culpability. I’m afraid of knowing where things come from.

These stirrings wrestle with me, tap against my temples every time I turn my key in the ignition or eat a piece of animal. Most of the time though, they’re so soft they slip beneath my frequency, and I go on unaffected. And then there’s my own wildness…even when I’m good at the game of playing grownup, I feel like a phony.

It seems every time I touch brush to canvas there comes a noise of techno-coloured frenzy. There’s a sea inside, and within those waters, an inertia spilling me onward. We’ll always be mysteries. Every breath, glance and conversation. We come from the inchoate void, leaping forward into song and shape, giving rise to the big questions: What are we doing here? How do I live best in this life? In this body?

In Christ all is reconciled. I want to take this seriously. All is reconciled. So there are no more dichotomies. My body and spirit are not in contradiction. Heaven and Earth are not mutually exclusive. My humanity does not separate me from the natural world. Some lie told me to turn away from the burning bush, to not get lost worshiping the earth. Now all I want is to belong to her, to, in the words of Raymond Caver, “feel myself beloved on the earth.” I wish for a consciousness of worship. I wish for a consciousness of awe, of reverence. I’m tired of the muted, when all of Creation constantly bursts with Holy Wow and we find ourselves incarnate, a part of the miracle. I want to feel connected; as much as I resist and dampen it, I want to be interrupted by interdependence.

I want to inhabit what Allen Ginsberg described as “mammal consciousness.” In interviews and lectures Ginsberg explored Western society’s systematic erosion of a consciousness of interconnectedness, which he believed is greatly feared by the economic mechanisms of the West. An all-pervading feeling of oneness with nature, with “the animals and the trees and the grasses” throws a wrench in the gears of an economic agenda bent on turning nature into lumber. What we do not respect, what we do not revere, we more readily devastate.

Ginsberg elucidates the matter as follows:

Because it’s a whole area of feeling, of communal family ritual feeling, which is feared. And the reason it’s feared is because it’s a breakthrough onto a new consciousness, which is not like the social consciousness inculcated by television or radio or newspapers or politics, it’s another mammal consciousness that’s unified with the world – you know, the consciousness that we share, the compassionate consciousness of the mind and the heart that we share with the bald eagles and the blue whales. And since we keep killing all the whales and the bald eagles it wouldn’t be appropriate to voice that consciousness – I mean it would be revolutionary to voice that consciousness, to articulate that consciousness and welcome it to the surface of front-brain awareness.

But voicing this consciousness is tricky at best. John Linton, who lives on a mountain in Southern Oregon where he teaches an interdisciplinary course of study, does a good job with his polar bear story. Of course, you’d have to sit with John, his black-rimmed hat covering his Einstein hair, to get the full impact. “So I’m sitting there,” he says, “and I suddenly realize that I’m killing the polar bears, that from miles away just by driving my car I’m killing them, and what do I do about that?” We need to be startled by these questions that challenge our conditioning. We need guides to help us through the dismantling.

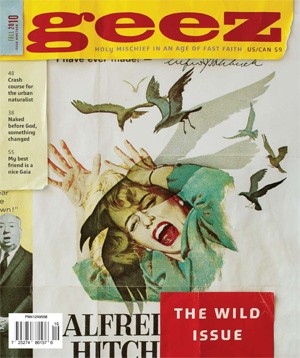

Used with permission Credit: flikr.com/photos/glamhag

The Oregon Extension, where John teaches in Lincoln, Oregon, gifted me a space of guides, books, thought-journey and wilderness. On that mountain in Southern Oregon I learned to love Gaia, to feel it as natural as the wildflowers growing around us. Even with a pastor mother who taught me inclusive language and sings the doxology accordingly, it’s still taken me a while to embrace my love of the mothering force thrumming through all of creation.

As a student in the Women Studies May Term at the Oregon Extension (co-guided by Nancy Linton, John’s wife), we studied our relationship with our selves, our bodies and our feminism, specifically in a Christian context, which we deconstructed, rejected and celebrated together. My project on Ecofeminism propelled me into a renewed relationship with Gaia, Mother Earth. Layers of detachment lifted

and I felt alive in Gaia, bound to her, aware of her sustaining mercy. Stilled, you can feel her infinite compassion. The world becomes a womb.

Gaia invites us into reciprocity and receptivity. We’re asked to be students and children, not dominators. The base of most major religions hinges on a compassion for all living things. Both Jesus and Buddha conveyed spiritual teachings illustrated by flowers. We’re asked to consider the lilies for how at home they are in their created being, and also to be considerate of them. Consider the wisdom of growing things – they know when to peek above ground. They feel when it is safe to do so. Consider them, be made wise by them. Walk humbly in this garden.

We’re detached and displaced from the natural around us and also from the natural inside us. We forget the self-regulating wisdom of our inner ecosystems. A friend who was recently sick with the flu commented on the body’s natural wisdom and healing system: “Your body, in an effort to kill the unwanted virus, puts itself through hell: raising the temperature, exhausting itself and soring the muscles. But it’s really amazing because the body is fully equipped to heal itself. It is pretty magical. No drugs needed.”

Of course the implications are widespread, calling us to rethink our relationship to all that is lab made. In our modern age this is a high order. The task is not to “return to the stone age,” but we must diligently challenge our notions of progress. How can we claim progress when the more we know the more we forget? In the midst of mass scale disruption of the Earth’s wisdom, we must turn towards

a feeling for the organism, towards the self-regulating mystery that pulses in all ecosystems and in our own bloodstream. The earth is not ours, but we are hers. The possessive form does not even apply here, for the earth does not own. We own. She holds.

Coming home to my body means coming home to the mud that made me – coming home to the mothering primordial wisdom and harmony of Gaia. I feel her pulsing.

I remember she’s a body. I ask to walk in compassion and consideration, with loving kindness for the soft moss and the cliffed edges. I ask to belong to the land.

Karis Granberg-Michaelson lives in Holland, Michigan, and works at a community creative play centre. Her wild side says to her, “For Gaia’s sake, paint more, stop apologizing, dance!, unbutton your heart, expand, remember me, smear mud on your skin, live in the jungle.”

Sorry, comments are closed.