A Heart Made Clean

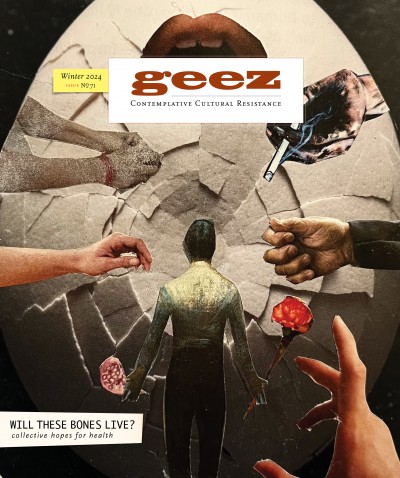

Detail of “And Despite Everything I’m Still Human”, Robert Valiente-Neighbours

On my first day as a student chaplain, I stood outside the Health Care for the Homeless Program (HCHP), suddenly terrified. I was six months pregnant. While I excitedly anticipated this placement for my Clinical Pastoral Education practicum, my idealism bumped up against my racism and privilege. HCHP was in a section of Washington, D.C. many said to avoid. I pressed the doorbell and waited to be let in while my mind and body urged me to flee.

It was the summer of 1995, over a decade into the AIDS epidemic. HCHP provided meals, counselling, and health care to unhoused men living with HIV. The placement felt like a perfect match as I had entered seminary, feeling called to serve as an HIV and AIDS chaplain. I came into adulthood when the AIDS epidemic was decimating communities marginalized by homophobia, racism, addiction, sexual exploitation, and poverty. Witnessing the AIDS quilt in front of the Washington Monument – the panels of names of the dead covering the size of a football field – affirmed my call to serve those ravaged by this terrible disease.

My awkward start continued once I entered the building. HCHP never had a chaplain before. Nurses and social workers had no clear role for me while they were busy caring for their clients. Even the director had little time for an overwhelmed seminarian. Eventually, he told me gently, “Just sit and listen.”

I sat at the table with the 20 or so men who had my pastoral care foisted upon them. At first, no one spoke to me directly. Then, one-by-one, they invited me into conversation, opening my heart as they opened theirs.

James shared stories of what he believed to be encounters with the devil, embodied by the drug dealer waving a packet of heroin on the street corner. He asked if I would pray for him to withstand this constant temptation.

Fred imagined the meals he would prepare in a home of his own, each ingredient carefully described.

Nathan, the one openly gay man, carried a gold lamé pillow to rest his arm, aching from the port inserted for his intravenous treatments. That pillow provided startling elegance amid the beat-up tables and ragged rugs.

Most beloved was Peanut, a small gentleman living with HIV who made us laugh with his wild stories. He withdrew into himself when he became diagnosed with AIDS. During my visits with him at the hospital, we silently watched the dialysis machine relentlessly clean the blood in his body.

Surprisingly, it was the new life I carried that connected us. The men shared stories of their children and grandchildren, of love and family – heartbreaking in loss and astounding in depth. I returned the following spring with my infant son to meet the men who blessed him so.

That summer, patients in the AZT trials experienced what some considered a miracle and called the “Lazarus effect.” Medical science transformed an HIV or AIDS diagnosis from a death sentence into a serious, but treatable, chronic condition. However, for those who suffered and died, and the many ignored and even outcast by their families and communities, the miracle didn’t come fast enough. It was too late for Peanut and several other men I came to know.

Standing in the stairwell that first day, I embodied the fear of being made “unclean” by people already outcasts, some even before being diagnosed with HIV or AIDS. Responding to God’s deeper call, I stepped through and found my heart transformed and humbled by these remarkable men – a heart made clean.

Ellen Rowse Spero lives in Acton, Massachusetts, with her spouse, Josh, and their two dogs. She has been serving the First Parish Unitarian Universalist Church of Chelmsford, Massachusetts since 2002.

Start the Discussion