Bodies of matter, bodies that matter

Messing up the mind/body distinction helps us make the move from bodies of matter to bodies that matter. But it’s more of a mish-mash than a one-way street. Our bodies are the true basis for our shared solidarity. But most of all our bodies are our homes. Let’s enjoy living there a while.

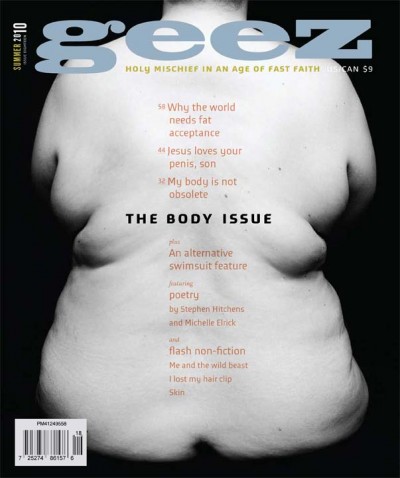

Yes, there’s a naked back on the front cover of this issue. If you think we did it to be provocative, you’d be right. If you think we did it to make you question your first response to seeing a fat body, you’d be right. But if you think it was all about the meaning of having a naked and fat body on the front cover, you’d be missing the point. (Or we wouldn’t be making it very well.) I hope you find this issue full of thought-provoking and interesting articles; maybe it will change your mind, or confirm something you already believe, or give you pause to consider the variety of human experience . . . but I also hope you enjoy it. I hope it simply gives you pleasure (or displeasure, as long it’s in the gut and not just the head). The cover is about beauty, about feeling and sensation, as much as it is about thinking and interpretation.

In Mad Men, the retro TV show about ’50s-era Madison Avenue advertising executives, women are housewives or secretaries, and men are out to take what they can get. So when Don Draper murmurs “This is all we have. This is all we get,” in Rachel Menken’s ear, it’s part and parcel of his seduction technique (she has a seduction technique of her own, but that’s a topic for another day).

What Don is saying is self-serving: he wants Rachel to forget about being a self-contained business heiress with ambitions, and for himself to forget about Betty and Sally and Bobby at home – to forget all those other commitments and alliances and desires and loyalties and duties beyond the one to the demands of the body in the moment. But really, isn’t he right? It’s his version of being a lily in the field: neither toiling nor spinning, nor worrying for the morrow nor remembering anything outside the now of warmth and touch, of hands undoing zippers and fumbling at buttons, of teeth and lips and tongues.

It’s one approach to the mind/body problem.

We have a long and bad habit of dividing the world into two and then deciding one half is better. The mind/body distinction is no different. So the body came to be seen as the lesser half: unreliable, subject to decay and corruption, impermanent and limited. All of which is true, and lent force to the association of the true and the good with the immaterial – with mind and spirit and soul. (This is the root of body-shaming in our culture.)

I find Don’s mantra worth repeating. I, too, want to seduce my busy mind and sink into the here-and-now of the body. But when Don whispers to Rachel, although he’s inverting the mind/body binary, he accepts the division between them. He’s valuing the body more than the mind, but he’s still buying into the either/or distinction.

As with all either/or distinctions, it is not the whole story.

When you start dividing the world into either/or, you have to keep lining things up on side or the other. So it goes with mind and body. Women, people of colour, and people with disabilities have historically been seen as closer to the body, to the earth, to what is weak and limited, what is further away from the mind and spirit. Part of the solution to this oppressive situation is to show that this is not true, that these folks have just as much claim to mind and spirit as anyone. That’s called upsetting the binary, but it’s not the whole answer.

The other part is to embrace what is being denigrated. To defiantly claim embodiment, not just for oneself, but for everyone.

When blogger La Labu comments: “We all have bodies. We all live in the world in our bodies. We perceive and are perceived via our bodies. And our bodies exist in a [hierarchical] plane where some bodies are more valued than others” – she’s not just making an abstract intellectual point. She’s writing out of her embodied experience – she’s taking seriously that she’s both body and mind. And it’s her body that taught her that. As it can teach us.

The work of anti-oppression movements is to recalibrate the system, so that no body is valued at the expense of another. That recalibration relies on hearing the voices of all kinds of bodies and their particular experiences and unique viewpoints. When you live in a body that gets less valued, you have a very clear perspective on the reality of embodied existence.

But don’t get me wrong – I don’t think of embodiment as primarily a teaching tool for some greater truth about justice. To do that would be to commit Don’s error, to buy into the dualistic distinction between minds and bodies. The body matters just because it is, not because it’s an appendage of a mind that can contemplate eternal truths.

Messing up the mind/body distinction helps us make the move from bodies of matter to bodies that matter. But it’s more of a mish-mash than a one-way street. Our bodies are the true basis for our shared solidarity. But most of all our bodies are our homes. Let’s enjoy living there a while.

Miriam Meinders lives in Winnipeg, Manitoba and is a member of the Geez magazine board. She loves salt and vinegar chips with chocolate milk.

Sorry, comments are closed.