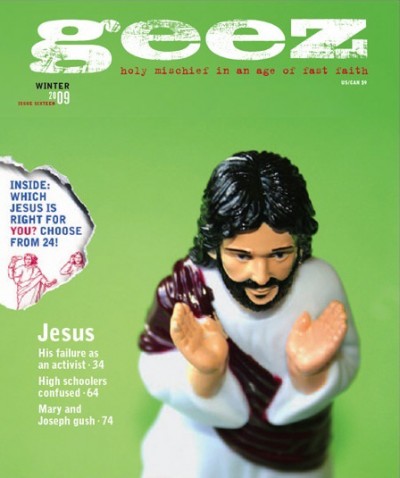

The case of the customized Christ

“If God created us in his image, we have more than reciprocated.” That’s what French philosopher Voltaire said of the human tendency to mould God into our own likeness.

Similarly, God’s son has been adapted to a great variety of human-created roles. To capitalist Christians, Jesus was a model entrepreneur. To socialist Christians, he was a hardcore socialist. To eco-Christians, he was a lily-loving environmentalist.

To self-help Christians, he was a motivational guru. And to Christian activists, he was a revolutionary. I used to fall into this last category. For much of the past decade I have been involved in social justice advocacy for marginalized people, and for many of those years I put my stock in the Jesus-as-activist characterization. But there was always some uneasiness about such a specific and selective interpretation of Jesus’ life. This discomfort has steadily increased. How can the story of Jesus shape me if I am so busy shaping it? While I see a link between social justice and the life of Jesus, it just feels too convenient to customize Jesus into an idealized version of my activist self. This leaves me at odds with fellow Christian activists who eagerly talk about Jesus as an activist.

One of the favoured cases for Jesus as a revolutionary is Ched Myers’ 1988 book, Binding the Strong Man: A Political Reading of Mark’s Story of Jesus. The 500-page commentary on the Gospel of Mark finds revolutionary politics at the heart of Jesus’ life. According to Myers, the “good news” in Mark is “a declaration of war upon the political culture of the empire.” The gospel is an activist manifesto that promises “to overthrow the structures of domination in our world.” Myers uses literary and cultural analysis to draw out the political and revolutionary meanings of Mark. For instance, he argues that Jesus’ call to be “fishers of men” is not a call to save souls but to “join [Jesus] in his struggle to overturn the existing order of power and privilege.” And when Jesus casts an evil spirit named “Legion” out of a man and then drives it into a herd of pigs that stampedes down a steep bank into the sea, Myers argues that the pigs represent the occupying Roman forces being driven out of Palestine. It’s all part of Jesus’ “war of myths.” Similarly, the concept of forgiveness is interpreted as an alternative to the temple sacrifices which required the poor to buy offerings they couldn’t afford. As for the many stories of healing, Myers explains them as “an essential part of [Jesus’] struggle to bring concrete liberation to the oppressed.”

Myers’ scholarship is helpful in highlighting the complex political significance of the Gospel of Mark. It leaves little doubt that Mark viewed Jesus as someone who boldly spoke out against exploitation, fought a battle of political myths, and engaged in “civil disobedience” (for example, openly violating Sabbath laws). But this is only one reading of one gospel. It is helpful and useful, but not if we take it as the exclusive lens through which to see Jesus. While I find much of what Myers writes affirming for me in my own activist efforts, instinct tells me that it’s more valuable to focus not on what I want to see but on what I may not want to see. It is the latter that can stretch me.

When I look at those parts of Jesus’ story to which I am less drawn, I see two main things that expand my sense of activist vocation: the caring, pastoral side of Jesus, and a conspicuous absence of success. First, the pastoral dimension. Jesus was a compassionate and dedicated shepherd. Even if the healings and forgiveness had political significance, surely they were also about simply caring for the immediate physical and spiritual needs of people. He was present to needy people and he created a community in which the neglected people of society found a place of belonging and inner wholeness. Task-oriented activists like myself don’t tend to talk much about belonging, pastoral care and being present to people. Efforts at structural change tend to trump, rather than accompany, efforts to create loving community centered around marginalized people.

The second aspect of Jesus’ life that pushes me in new directions is the fact that he quietly submits to an entirely unjust death and then leaves the earth before accomplishing a revolution or achieving activist success of any sort. If Jesus were the archetypal activist, I would have expected him to accomplish successful land reform, remove the Roman occupiers from Palestine or make poverty history. While he did many kind things for exploited people (as well as for some exploiters), and while he offered an incisive critique of the oppressive structures of his day, at the climax of the story he does not play what would have been his ultimate activist trump card: to appear to the authorities in his risen form to lobby, convert or depose them. Instead, Jesus quickly exits the scene and the Romans, along with the corrupt Jewish ruling class, remain intact. If Jesus is a model for activism, he seems to be a model for failed activism.

Consider Jesus’ so-called triumphant entry into Jerusalem. Commentators suggest that anti-Roman rebel movements were common in Jesus’ time and the crowds who cheered him as he rode into Jerusalem likely hoped Jesus would lead a successful political revolution. They projected their activist aspirations onto him. But those expectations quickly proved entirely misguided. Jesus ended up slouched on a cross, not leading a victorious revolt.

Though the resurrection – with its layers of meaning – was a victory of sorts, it did not achieve the type of ends most of us activists work toward. The meekness of Jesus as he is condemned and crucified is hardly the posture that activists usually emulate.

I should note that Myers also considers the cross a “failure” by revolutionary standards. For him, this failure leaves room for us to continue the story in communities of “radical discipleship” and inclusion. And he concludes that Jesus’ submission to death on the cross teaches that the powers can only be countered with symbolically charged non-violence.

When I look at Jesus’ track record as an activist, and the rather non-activisty pastoral dimension of his life, I am led to a somewhat different (though not entirely contradictory) conclusion. My conclusion, tentative though it may be, is that Jesus’ primary focus was not activism or revolution as we commonly understand those terms. It was broader, more nuanced, more mystical perhaps. In my own efforts to live into a vocation broader than standard goal-oriented activism, I find helpful examples in the lives and writings of Caryll Houselander and Oscar Romero.

Caryll Houselander – a Catholic mystic, writer and companion of the needy in England – demonstrated pastoral presence and holy failure in the midst of oppression. While working as a nurse during the chaotic violence and suffering of the World War II bombing raids in London, she wrote the following:

‘It came to me like a blinding flash of light that Christ did not resist evil, that he allowed himself to be violently done to death, that when he gave himself to be crucified, he knew that the exquisite delicacy and loveliness of the merest detail of Christian life would survive the Passion, that indeed … it depended on it. And so it is now: that which is holy, tender and beautiful will not be swept away or destroyed by war.”

The story of Jesus did not hold for her the promise that the bad guys would be overthrown but that there were certain things that live on beyond the reach of the destructive powers. The poetry of life itself will be resurrected no matter what.

Romero was another example of a response to oppression that went deeper than activism. He was Archbishop of El Salvador in the late ’70s, a period during which peasants and priests who opposed the oppressive powers were being disappeared and murdered. While he spoke with great conviction and eloquence against the injustices of his time – to the extent that he too was assassinated – he remained more of a pastor than an activist. While legitimizing the concrete needs of the peasants, he warned the more activist-minded in his flock that an ideal “political and social order” would not be complete unless people’s hearts were converted to “deep joy of spirit” and peace with God and each other.

Despite giving his life, he failed to stop the repression or prevent civil war. But he both named the essence of the powers and fostered a spirit that no bullet could hit, famously declaring shortly before his death: “If they kill me, I will rise again in the Salvadoran people.”

As I look beyond the Christian activist model, I ask myself three questions that, for me, arise from the story of Jesus. First, what is the incisive word and the symbolic sacrifice required in the present-day battle of political myths? Second, how can I contribute to a community of physical and spiritual caring? And finally, in all my efforts, how can I best nurture the holiness, tenderness and beauty that will live on even when the powers prevail?

Will Braun is a former and founding editor of Geez. He can be reached at wbraun@inbox.com.

Sorry, comments are closed.